Investment and growth in advanced economies: selected takeaways from the ECB’s Sintra Forum

Contribution of Vítor Constâncio, Philipp Hartmann and Peter McAdam for VoxEU

The European Central Bank’s 2017 Sintra Forum on Central Banking built a bridge from the currently strengthening recovery in Europe to longer-term growth issues for and structural change in advanced economies. In this column the organisers highlight some of the main points from the discussions, including what the sources of weak productivity and investment are and what type of economic polarisation tendencies the new growth model seems to be associated with.

This year’s ECB Sintra Forum on Central Banking focused on the major real economy developments that surround and interact with monetary policy. Policymakers, academics and market economists debated on the topics of innovation, investment and productivity as well as business cycles, growth and associated policies. In this post we summarise six of the main themes that were keenly discussed in Sintra in June 2017: explaining the global productivity slowdown; the implications of technical progress for employment; explaining the laggard post-crisis recovery; sources of weak investment; the complementarity between demand and supply policies; and relevant aspects of the broader societal context. The full set of papers, discussions and speeches can be found on the Sintra Forum website while video recordings of all sessions are on the ECB’s YouTube channel.

Explaining the productivity slowdown: techno-pessimism, fading research effort or mismeasurement?

“Perhaps the most remarkable fact about economic growth in recent decades is the slowdown in productivity growth that occurred around the year 2000,” said Chad Jones (2017) in motivating his Sintra contribution. This phenomenon, which has affected many advanced economies, has been widely argued for a number of years and may have become more pronounced following the financial crisis (e.g. OECD 2015, Adler et al. 2017). Jones suggests studying the sources of this slowdown via the two main forces that explain productivity in modern growth theory: innovation and the misallocation of production factors. Regarding the latter, Jones (2017) reports key results of the literature that associates the dispersion of marginal products of the same factors across firms in the US and in Europe with degrees of misallocation (e.g. Gopinath et al. 2017, highlighting deteriorating factor allocation in Italy and Spain). A recent paper by Bils et al. (2017) suggests, however, that if one corrects for measurement error, the entire increase of allocative inefficiency in US manufacturing since the late 1970s disappears. It may therefore be advisable to wait until measurement errors are also accounted for in the literature on non-manufacturing sectors and on Europe before drawing clear-cut conclusions.

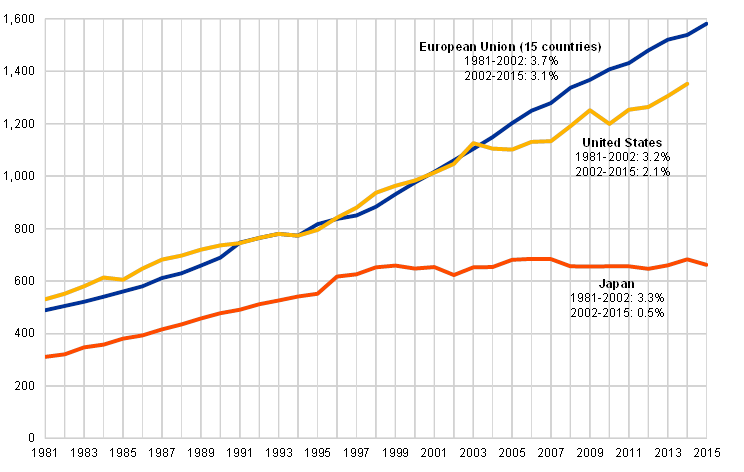

Regarding innovation Jones argues that their contribution can either be driven by the impact of new ideas and processes on total factor productivity (“ideas TFP”) or the research effort pushing new ideas (such as the number of researchers employed). Gordon (2016), for example, suggested for the US that ideas with the same productivity benefits are harder to discover today than in history. Jones – in joint work with Bloom, Van Reenen and Webb (2017) – finds that this is a rather general phenomenon across different sectors and products, detecting significant reductions in “ideas TFP”. Over many decades, however, this was compensated by over-proportionate increases in research effort. As research employment growth has slowed down since the early 2000s – mostly in Japan, significantly in the US and to a lesser extent in the European Union (see Figure 1) – the phenomenon has become more harmful today than it used to be. This can explain the productivity slowdown and is consistent with Gordon’s thesis. But it puts the emphasis on ways on how to maintain a sufficiently high research effort.

Figure 1. Development of research efforts

Note: The lines show the logarithms of the total number of researchers (in 1,000s), so that their slopes reflect growth rates. The text insertions show annual growth rates for two sub-periods, respectively.

Source: Reproduced from Jones (2017), Chart 4, who uses OECD Main Science and Technology Indicators.

On historical grounds, Joel Mokyr (2017) challenged the view that it is the nature of today’s innovations that accounts for the productivity slowdown and staged a forceful rebuttal of “techno-pessimism”. First, economists’ primary measures of innovation – estimations of total factor productivity and counting of patents – both underestimate their productivity effects. Second, in history humans have overcome the fact that the technological fruits that can still be picked are hanging higher and higher through building “taller and taller ladders”. This “arboreal metaphor” illustrates a feedback from technology to science. The technological tools detected over centuries that made that possible included the telescope, the microscope, the eudiometer or, more recently, x-ray crystallography. Two prominent and powerful tools today are laser technology and computers. The “hot technology of the day” is machine learning – according to Hal Varian (2017) – and quantum computing is on the way. So, Mokyr does not see why the growth in economic welfare should slow down for technological reasons. In this context, it was interesting that an online poll showed that 72% of voting Sintra participants felt that the productivity gains from the ICT (information and communication technology) revolution will accelerate, given that its full potential has not emerged yet. Reinhilde Veugelers (2017) added that it is diffusion that makes innovation such a powerful growth engine. She referred to recent evidence produced by the OECD suggesting that the diffusion and adoption of the latest technology across firms may be more of a problem than a lack of innovation as such (Andrews et al. 2015). (This point had already been much emphasised by Mario Draghi and Catherine Mann at the 2015 ECB Sintra Forum; see Constâncio et al. 2015.) She reckoned that the most potent mechanism for the transfer of new know-how is when the innovating researchers move from frontier firms to other sectors or firms.

In addition to Mokyr, several other speakers also considered measurement problems affecting productivity assessments, e.g. through the underestimation of GDP (the numerator of aggregate productivity measures). Jones (2017) and Varian (2017) referred to software or services provided for free or at very low prices by ICT firms or not-for-profit institutions (e.g., Facebook, Google or Wikipedia). The problems are particularly pronounced in areas involving rapid quality change, such as photography, the global positioning system (GPS) or, more generally, the smartphones in which these and many other applications are embedded. At zero or near-zero prices, hedonic quality adjustments in nominal national accounts are difficult. Recent literature, such as Byrne et al. (2016) or Syverson (2017), however, argues that the “free” services and other ICT features only account for a small part of the productivity slowdown in the US. Based on the practice of statistical agencies to impute value developments of disappearing products from value developments of surviving products, Philippe Aghion presented in Sintra sizeable growth underestimation for France and the US, amounting to slightly more than half a percentage point of measured annual growth (see Aghion et al. 2017b for the US). But Jones (2017) points out that the authors do not find a substantial change over time, which would be required to provide an explanation for the measured productivity slowdown around 2000.

All this led to a debate about the relative roles of the private and the public sector in innovation. Reinhilde Veugelers (2017, Chart 1) showed that the European Union is particularly weak in business research and development (R&D; constituting only about 1% of GDP) relative to major advanced and emerging economies, having even fallen behind China over the last decade. Chad Jones (2017, Chart 3) showed that after large contributions in the late 1950s and 1960s, government R&D has become much less important in US intellectual property investments over the last decades. This evidence led Simon Johnson (2017) to identify the government as “a primary culprit” for the US losing its world technological leadership and the growth and employment that went along with it. He called for increased public spending on basic scientific research and the creation of new technology clusters, based on local expertise and specialisation, and co-funded by the federal government. Mariana Mazzucato promoted mission-directed government investments in innovation (one example being the US Apollo programme of the 1960s and early 1970s), which “co-shape and co-create markets” and benefit from patient long-term strategic financing (Mazzucato and Semieniuk 2017). She was sceptical of indirect forms of financing, such as tax advantages, which may enhance profits without necessarily ensuring “additionality”. Dietmar Harhoff (2017) concurred that the preferential treatment of intellectual property, such as “patent boxes”, amounted to beggar-thy-neighbour policies with little positive impact on innovation.

Does technical progress create or destroy jobs?

One of the fundamental tenets of growth theory, underlined by the discussion summarised in the previous section, is that technical progress makes long-term per capita growth possible in equilibrium (Solow 1956, 1957). But recently concerns have arisen that the technical advances of our times may be particularly destructive in replacing jobs (the dystopian variant of techno-pessimism, according to Joel Mokyr (2017)). David Autor and Anna Salomons (2017) forcefully argue that this has not been the case in history, despite such concerns having emerged periodically over the last 200 years. Covering 19 advanced economies between 1970 and 2007, they find that productivity growth has been mildly positive for aggregate employment. Their country-industry panel regressions suggest that – over long periods of time – the negative effect of productivity growth on employment in the same industry is more than compensated by positive “spillovers” in terms of expansions in other industries. Thus, structural change triggered by technical progress, ultimately, creates more employment in new sectors than it destroys in old ones.

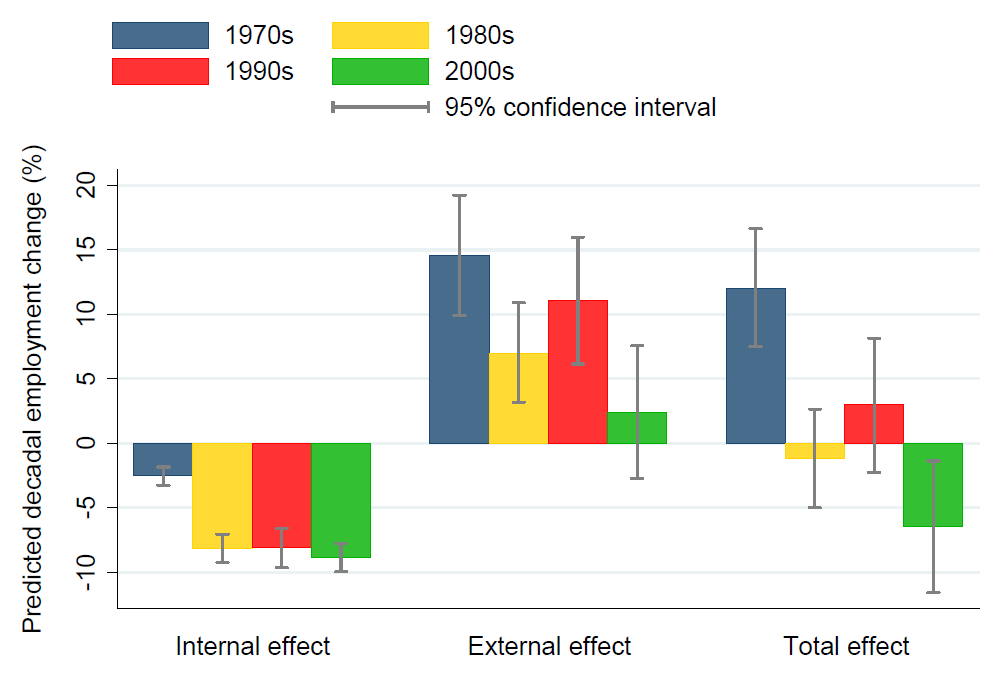

Does this pattern change over time? Figure 2, taken from Autor and Salomons’ (2017) Sintra paper, compares the estimated own (“internal”) industry effects, the external effects on (or spillovers to) other industries and the net effects for four different decades. In line with the pooled results, the internal effects are consistently negative and the external effects consistently positive. In the 2000s, however, the positive external effects are so small that the net effects turn negative. Whether this means a reversal of the historical pattern is open to debate. The authors indicate that as early as in the 1980s negative and positive effects were basically cancelling each other out but strong positive spillovers returned in the 1990s. Moreover, preliminary follow-up work with a different database going up until 2014 seems to suggest that another recovery of the benign productivity-employment relationship may have emerged (though these results could be subject to change). Ultimately, only the future will tell. Indeed, another online survey showed that participants of the Sintra Forum were divided on this issue. 43% of voters indicated that technological innovation will have an insignificant impact on employment in the next 10 years. 28% felt that the net impact would be positive and an equal share that it would be negative.

Figure 2. Effects of productivity on employment

Note: The bars show cumulative percentage employment changes for four sub-periods as predicted by productivity growth in five sectors (utilities, mining and construction; manufacturing; education and health; high-tech services; and low-tech services) from estimating equation (7) in Autor and Salomons (2017) as reported in their Table 8. “Internal effect” describes the effect of industry productivity changes on employment in the same industries. “External effect” describes the effect of industry productivity changes on employment in all other industries. “Total effect” is the net effect of these two. The sample comprises 19 industrial countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, Japan, South Korea and Australia) and covers, for most of the countries, the period between 1970 and 2007. Productivity is gross output per worker. Predictions for the 1970s and 2000s are scaled up to be comparable to the 1980s and 1990s.

Source: Reproduced from Autor and Salomons (2017), Figure 7.

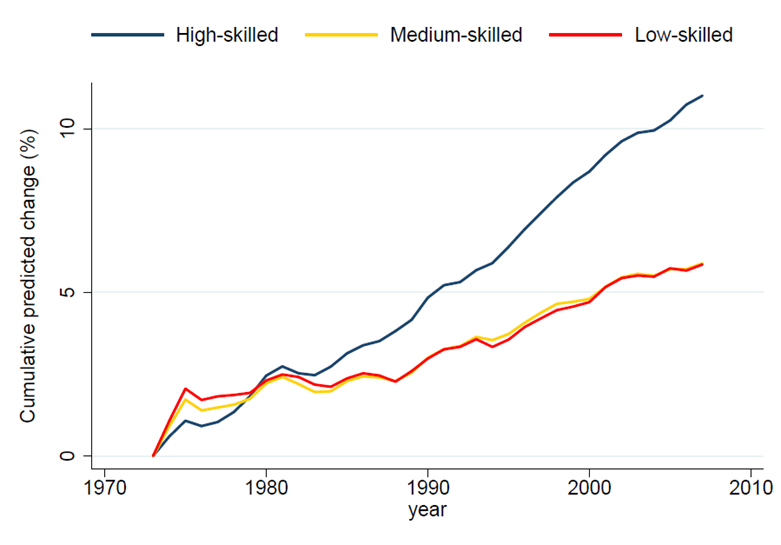

Interestingly, the historical productivity-employment nexus is quite different across sectors. For example, the strongest positive employment spillovers originate from productivity growth in low-tech services (capturing e.g. car sales, real estate, hotels and catering or social and personal services). Significantly positive spillovers also emerge from high-tech services (e.g. telecommunication and financial intermediation) as well as health and education. Autor and Salomons do not find significant external effects of other sectors. More worrying, however, are their results on the effects of productivity growth on the composition of labour demand. They find clear evidence of “polarisation” in the group of 19 advanced economies in that most new jobs were – on average – created for highly skilled employees, whereas jobs for medium or low-skilled workers grew slowly (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effects of productivity on employment by skill group

Note: The lines show cumulative average changes in employment shares for three skill groups as predicted by productivity growth in the same five sectors as listed in the note to Figure 2 from estimating equation (8) in Autor and Salomons (2017) as reported in their Table 9. The sample comprises the same 19 industrial countries as listed in the note to Figure 2. Productivity is gross output per worker.

Source: Reproduced from Autor and Salomons (2017), Figure 8.

Explaining the slow post-crisis recovery: demand or supply?

While slower productivity advances may have been weighing on economic growth since the early 2000s, it cannot explain why recoveries towards potential growth were so weak and slow. Bob Hall (2017) tries to identify sources of stagnation tendencies in his Sintra paper by looking at developments in real earnings per member of the population in six major advanced economies (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States) between 2000 and 2014. He regards this as a particularly suitable metric, because it measures the well-being of a majority of populations. In the seven years following the start of the financial crisis, Germany in particular but also France appear to have experienced little stagnation, with positive annual growth rates of labour earnings. The most stagnating economies were Italy and Spain with negative annual growth rates of almost 2%, whereas the UK and the US saw more moderate stagnation.

Hall suggests assessing the plausibility of factors explaining stagnation tendencies by decomposing real earnings per capita into seven components (the labour share of total income, multifactor productivity, the capital-output ratio, hours per worker, the employment rate, the labour-force participation rate and the ratio of working-age population to total population). Table 1, taken from his paper, shows the annual growth rates for five of these components between 2007 and 2014. First of all, the many green (favourable, mostly positive values) cells in the first row illustrate the relatively positive developments for German workers. Second, the declining labour share in total income (see first column “Share”) is a broad-based international problem, which Hall characterised as “the hot topic in quantitative macroeconomics”. (Not only is it present in the US, many European countries and Japan but also in China; see Karabarbounis and Neiman (2014), Figures II and III, and Hall 2017, Figure 2). Third, protracted unemployment weighs particularly on labour earnings in Southern Europe (“Employment rate” column). The primary stagnation factor in France is the labour share while in the UK it is productivity. Finally, the single red (negative value) cell in the last column (“Participation”) suggests that declining labour market participation is a problem that is very much in evidence in the US.

Table 1. Development of stagnation factors after 2007

Note: Numbers in the cells show the average annual growth rates of five components of real labour earnings per member of the population between 2007 and 2014. “Share” stands for the labour share of total income, “Productivity” for multifactor productivity, “Hours/week” for weekly hours per worker, “Employment rate” for the share of workers in the labour force and “Participation” for the share of people of working age in the total population. Green cells highlight favourable growth rates (usually positive) and red cells unfavourably large negative growth rates. The strength of the colour reflects the degree to which the respective growth rate is favourable or unfavourable.

Source: Reproduced from Hall (2017), Table 9.

From the large diversity across countries and labour income components, Hall (2017) finds it implausible that “unitary theories” of stagnation can explain these empirical facts. Rather, each country seems to have its own story, involving particular patterns of factor shares, productivity growth, unemployment, labour supply and demographics. Moreover, many of the key factors are not of a cyclical nature and therefore cannot be effectively cured with expansionary monetary policy. Instead, some of them belong to supply components, such as labour participation or productivity, to which policy attention should turn, in Hall’s view.

Gauti Eggertsson (2017) challenged this, based on a different reading of the facts. Referring to a host of previous papers, he argued that New Keynesian secular stagnation theory can make a valuable contribution to understanding the slow post-crisis recovery. First, the financial crisis may have involved an aggregate demand shock that lowered the real natural rate of interest, so that the effective lower bound of interest rates prevented central banks from exercising enough monetary policy stimulus. The resulting low inflation and growth in the euro area, the UK and the US would go hand-in-hand with sub-par labour income growth. Second, the effect of the crisis may have been asymmetric in the euro area, with Germany being less negatively affected. So, the common ECB monetary policy may have been consistent with the full utilisation of labour inputs in Germany, in Eggertsson’s view, but insufficiently expansionary for Italy or Spain. Third, Eggertsson was not convinced that divergent labour market or productivity outcomes could not be explained by demand factors as well. For example, different labour market institutions could lead to different degrees of “labour rationing” across countries. Moreover, if innovation is endogenous hysteresis effects of a demand-led recession could lead to a protracted slowdown in productivity (e.g. Garga and Singh 2016).

An online survey suggested that 36% of voting Sintra participants thought that mostly aggregate demand and 18% that mostly declining supply trends were responsible for the slow economic recovery. Interestingly, 38% pointed to a protracted debt overhang that affects deleveraging and demand. The relatively favourable labour income developments in Germany prompted several Sintra participants to offer their own explanations. Volker Wieland explained that the phenomenon started before the financial crisis, around 2005, when the lagged effects of previous massive tax reductions, labour market reforms and a focus of the unions on job security rather than wage growth healed Germany’s economy – at the time “the sick man of Europe”. Thereafter, Germany developed a low-wage services sector that hurt productivity through a composition effect but at the same time greatly expanded employment. In other words, it was an example of a supply-side policy that created demand, supporting Bob Hall’s conclusions. In a similar vein, Michael Burda added that Germany increased labour force participation via part-time work arrangements. Since total hours worked hardly changed, this acted like work sharing. There was an increase in wage dispersion but little movement in wage levels. Workers had to accept this due to the labour market reforms, which cut unemployment benefits and their duration, and thereby increased incentives through replacement rates (the ratio of unemployment income and expected income when employed). All not a miracle, Burda said, just neoclassical economics working the right way.

Investment gap? The roles of product market competition and intangibles

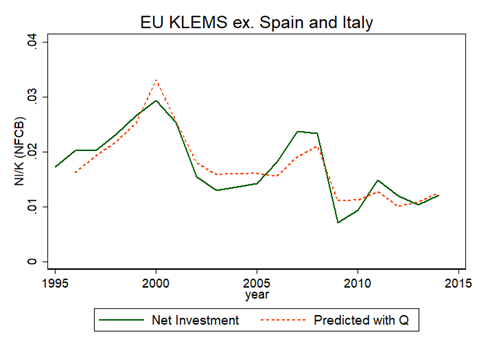

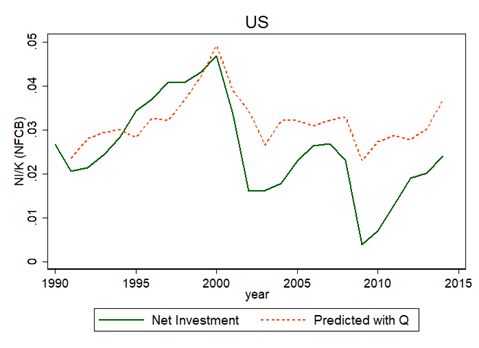

One of the distinct features of the deep and long recession caused by the twin (financial and sovereign debt) crises and the slow recovery in Europe has been weak investment. Thomas Philippon, in collaboration with Robin Döttling and Germán Gutiérrez (2017b), explored the causes of this phenomenon, comparing primarily a group of eight euro area countries with the United States. They first establish a number of stylised facts: 1) the corporate investment rate was low in both the euro area and the US, with the share of intangibles (investment in intellectual property such as computer software and databases or research and development) increasing and the share of machinery and equipment decreasing; 2) corporate profits were low in the euro area and relatively high in the US; 3) Tobin’s Q (e.g. Tobin 1969) was relatively low in the euro area – explaining corporate investment well (in particular if one excludes Italy and Spain) – and relatively high in the US but underpredicting investment there. The latter finding – that there is an “investment gap” at the aggregate level in the US but not in Europe – is displayed in Figure 4, where in the upper panel the dashed red line tracks investment rather well and in the lower panel investment is lower than what Q would predict.

Figure 4. Explanation of investment with Tobin’s Q

Panel a. Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany and the Netherlands

Panel b. The United States

Note: The lines in both panels show the measured net investment rate of the non-financial corporate sector and the net investment rate predicted by a regression of net investment on the lag of Tobin’s Q. The vertical axis is in fractions. Net investment is measured as gross fixed capital formation scaled by the lagged stock of fixed assets (“gross investment rate”) minus gross fixed capital consumption (i.e. depreciation). Tobin’s Q is measured as the market value of equity plus total liabilities minus financial assets divided by the sum of the stock of produced and non-produced assets (which includes tangible and intangible capital). The “euro area” in Panel a. comprises only five countries for data limitations and since Italy and Spain have been excluded because the relationship between investment and Q is different for them.

Source: Reproduced from Döttling, Gutiérrez and Philippon (2017), Chart 11.

As is well known, Tobin’s Q is defined as the market value of a firm’s assets (typically measured by its equity price) divided by its accounting value or replacement costs. Under certain assumptions, it should capture the main economic fundamentals determining investment. Therefore, Döttling, Gutiérrez and Philippon (2017b) infer from fact 3) above that weak aggregate demand and low expected future growth must explain the low Q in the euro area, which in turn explains most of the aggregate euro area investment slump (notably in Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany and the Netherlands, but not in Italy or Spain). In contrast, the general economic environment as reflected in a high Q does not explain weak US investment, which must be due to other, more structural factors. Building on previous work (Gutiérrez and Philippon 2016), the authors observe that the opening of the aggregate investment gap in the US around 2000 coincides with the start of a trend in corporate concentration and a reduction in antitrust enforcement in the country. (Regulatory reforms in many euro area countries, however, made their product markets more competitive during the 2000s.) Moreover, given high corporate savings (see fact 2) above; see also Eberly 2017, Chart 2), it is not plausible that financial constraints played a large role in the US (except perhaps at the height of the financial crisis). Finally, the share of intangibles in investment is unlikely to explain the difference between the US and the euro area, because its growth was slowing in the early 2000s (see e.g. Eberly 2017, Chart 1, or Jones 2017, Chart 3) and Europe’s share catching up since the late 1990s (Döttling et al, 2017b, Chart 15). In sum, Philippon et al. conclude that deteriorating product market competition is likely to be a major factor in explaining the aggregate US investment gap. But structural features, probably other than corporate concentration, also seem to be of relevance in explaining the investment gaps in Italy and Spain. There is no comparable corporate concentration trend in Europe, but Reinhilde Veugelers (2017) observed that research and development (R&D) expenditures become more concentrated in fewer firms. It needs to be determined whether this R&D concentration is simply a sign of the advantages that leading technological firms may have in terms of efficiency; or whether it may in fact become an obstacle not only to the diffusion of ideas but also to new entrants in the future.

As several Sintra authors elaborated, intangibles generally play an increasing role in investment. This is particularly a consequence of the prominent role that digitisation, information and communication technology play in what is often called the third industrial revolution. But in the US a pronounced trend started as early as in the 1950s (see Eberly 2017, Chart 1, and Jones 2017, Chart 3). Once the fixed costs of IT hardware have been paid, human capital and intellectual property gain importance relative to physical capital. This can affect investment and its determinants in various ways. First, as Philippon et al. suggest, intangible assets are more difficult to accumulate quickly, which is tantamount to higher adjustment costs. So, in equilibrium, rising intangible investment should lead to rising Q. Second, Enrico Perotti pointed out that high-intangibles firms pay highly skilled employees to invest their human capital (e.g. to develop software) and therefore do not need to undertake as much traditional investment spending as low-intangibles firms (see Döttling et al. 2017a). In fact, the investment share of some of the most innovative and rapidly growing sectors in the US, namely the high-tech industries, is rather stagnant (Eberly 2017, Chart 3). Third, intangible investments are beset with measurement problems, so that they could be underestimated in available data. All in all, the negative relationship between the share of intangibles and total investment that emerges from this list is consistently confirmed in empirical estimations (Eberly 2017), including (for cross-sectional industry data) in Europe (Döttling et al. 2017b). So, part of the low investment observed in countries with rapidly growing intangible shares, such as the euro area countries covered in Döttling et al., may not be a sign of economic weakness but a sign of structural change and difficulties in capturing intangible investment in available data. But growing intangibles could still be a contributing factor to labour market polarisation, because the employees producing them tend to be highly skilled and paid (see Section 2 above).

Relationships between demand and supply policies

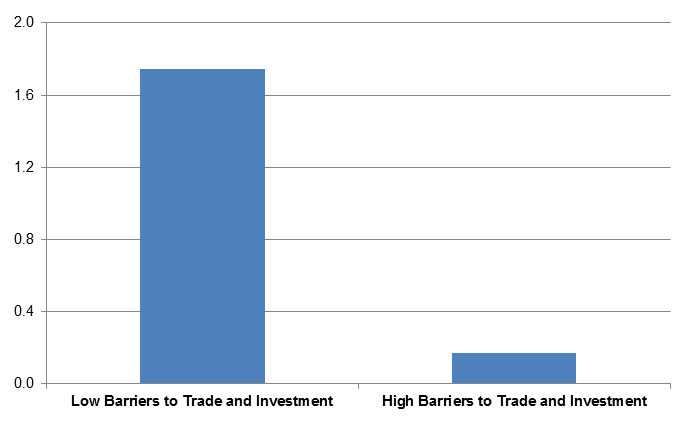

The Sintra discussions about the slow post-crisis recovery and the role that investment played in it suggest that both supply and demand policies have a role to play, depending on the country and time considered. But demand and supply policies do not need to be substitutes: they can be complements. Philippe Aghion, in a joint paper with Emmanuel Farhi and Enisse Kharroubi (2017a), crystallised this with the example of monetary policy and product market reforms, bolstering President of the ECB Mario Draghi’s (2014) view that “aggregate demand policies will ultimately not be effective without action in parallel on the supply side”. With two different empirical approaches they find that countercyclical interest rate movements become more effective in stimulating output when product markets are more competitive. The first approach starts by estimating the countercyclicality of real short-term interest rates (for the euro area, the area-wide nominal rate divided by national inflation rates) in response to output gaps at the level of 14 advanced economies (9 euro area countries, 3 other EU countries, and Australia and Canada). The second step of this approach is to interact the estimated countercyclicality parameters with measures of firm financial constraints and product market regulation. As long as the 1998 level of the OECD indicator for barriers to trade and investment is low, it turns out in a country-industry panel regression of quarterly data between 1999 and 2005 that a sector with high labour costs to sales (as a measure of firms’ financial constraints) located in a country with high interest rate countercyclicality exhibits a 1.6 percentage points higher real value-added per worker growth than a sector with low labour costs to sales in a country with low interest rate countercyclicality (see the left blue pillar in Figure 5). In contrast, when product market regulation is heavy, then this growth difference evaporates (right pillar in the figure).

Figure 5. Joint effects of the countercyclicality of interest rates and corporate financial constraints on labour productivity for different degrees of product market competition

Notes: The blue bars show the estimated effects of the responsiveness of real short-term interest rates to output gaps (“countercyclicality of interest rates”) and financial constraints in corporate sectors on labour productivity in 14 advanced economies (excluding the US benchmark, they are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, the UK, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden) between 1999 and 2005. The countercyclicalities of interest rates are estimated for each country in separate regressions (and reported in Figure 1 of Aghion et al. (2017)). These country elasticities are then inserted in a cross-country cross-industry panel estimation of productivity in which they are interacted with the ratio of labour costs to sales in the corresponding US industry (as a measure of financial constraints) and a dummy variable for the OECD indicator of barriers to trade and investment (in 1998 as an inverse measure of product market competition; see Aghion et al. (2017), Table 1). Labour productivity is real value-added per worker growth. The two bars show the change in labour productivity in response to a joint change from the first quartile to the third quartile in the industry distribution of financial constraints and from the first to the third quartile in the country distribution of the estimated countercyclicalities of interest rates, once for high (low barriers) and once for low product market competition (high barriers). The vertical axis is in percentage points.

Source: Reproduced from Aghion, Farhi and Kharroubi (2017a), Figure 2.

The second approach takes the ECB’s announcement of its Outright Monetary Transactions programme (OMT) in September 2012 as a laboratory. It first estimates forecast errors for 10-year government bond yields of 7 euro area countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain) for the periods 2011-12 and 2013-14, i.e. before and after the OMT announcement. The difference between the two is taken as surprise changes in firms’ funding costs. Stressed countries, such as Italy and Spain, experienced sharp unexpected interest rate drops but the same did not apply to other countries, such as France or Germany. Then a difference-in-difference estimation of industry growth rates for 2013-14 for the 7 countries on industry growth rates for 2011-12, corporate indebtedness (measured in 2010 and 2012, respectively) and interactions between corporate indebtedness, product market regulation (same OECD indicator as in the first approach but for 2013) and the estimated OMT interest rate surprises is conducted. The results suggest that heavily indebted corporate sectors grew faster as a consequence of the large surprising interest reductions, but only when they were located in countries with relatively less regulated product markets. This effect works primarily via short-term debt, which firms can adjust more quickly than long-term debt. It may, however, be attenuated by an uncompetitive banking sector.

Marco Buti (2017) addressed the relationship between demand and supply policies from a fiscal policy angle. He juxtaposed two views on the relationship between fiscal consolidation and structural reforms, one where they are substitutes (e.g. because the temporarily unemployed from labour market reforms would have to be supported) and another where they are complements (e.g. because expansionary demand policies diminish governments’ incentives for introducing politically costly structural reforms). Buti showed recent European evidence supporting the latter view. Before the crisis there was no clear relationship between primary cyclically adjusted budget balances and reductions in employment protection. But with the sovereign debt crisis a positive relationship emerged (see his Chart 2). He argued, however, that the complementary approach may not be the right model for the future, because of rising inequality and fiscal consolidation leading to reduced public education spending and the reforms that are most needed, i.e. the ones stimulating innovation and productivity, having significant budgetary costs.

When growth is not enough: inequality and the greater societal context

Introduced by a haunting plea from Ben Bernanke (2017) in his dinner speech “When growth is not enough”, some of the Sintra discussions branched out to distributional issues and the societal context that influences the environment in which central bankers, much like other policymakers, act and economic policies are conducted. Bernanke stressed that the continuing structural change when the unusually prosperous post-WWII period in the US “normalised” as of the 1970s was not accompanied by supportive labour market and social policies. Over time, popular dissatisfaction about the economic situation emerged related to stagnating earnings per worker, declining social and economic mobility, social dysfunctions such as drug abuse and distrust of political institutions. Rectifying the situation requires interventionist policies, such as community re-development, infrastructure spending, job training and addiction programmes. For Europe, Bernanke recommended that the continuing labour market reforms that are necessary should be accompanied by training and other work force development; that structural reforms should be accompanied by demand policies; and that political legitimacy should be ensured through subsidiarity. Whilst against the background of ever faster technical progress and structural change it was relatively uncontroversial that the traditional “once-in-a-lifetime schooling strategy” has to give way to continuous updating of knowledge and skills (“lifelong learning”), Dietmar Harhoff (2017) warned that so far there is little systematic implementation and institutional development.

Sergei Guriev (2017, Chart 1) presented “elephant curves” (à la Milanovic 2016), suggesting that the crisis recession acted in a regressive way in southern European countries (see also Buti 2017, Chart 3), whereas in other euro area countries asset price declines implied that the recession’s cost were mostly borne by the better-off. But in terms of popular support for economic policies, Guriev (2017, Table 1) provided evidence that it is not inequality per se but perceived “unfair” inequality (defined as uneven opportunities, such as parental background, gender, ethnicity or place of birth) that leads to the rejection of a market economy (and also corruption). Other factors captured in the residuals of the estimation, such as lack of effort or bad luck, do not have this effect.

Agnès Bénassy-Quére (2017) perceived an imbalance in Europe between trade and competition policies being centralised at the area-wide level but social and tax policies being left at the national level. When the federal level promotes free trade and competitive markets, then Member States are left to bear the social consequences. In her view Member States could be better empowered by coordination in tax and social policies. One idea is to make the EU’s Globalisation Adjustment Fund more effective; another is to introduce US-style TTTTs (timely, temporary, and targeted transfers).

References

Adler, G., Duval, R., Furceri, D., Kiliç Çelik, S., Koloskova, K. and Poplawski-Ribeiro, M. (2017), “Gone with the headwinds: global productivity”, IMF Staff Discussion Notes SDN/17/04, April.

Andrews, D., Criscuolo, C. and Gal, P. (2015), “Frontier firms, technology diffusion and public policy: micro evidence from OECD countries”, The Future of Productivity: Main Background Papers, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

Aghion, P., Farhi, E. and Kharroubi, E. (2017a), “On the interaction between monetary policy, corporate balance sheets and structural reforms”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Aghion, P., Bergeaud, A., Boppart, T., Klenow, P. and Li, H. (2017b), Missing growth from creative destruction, mimeo, Collège de France, Paris, July.

Autor, D. and Salomons, A. (2017), “Robocalypse now: does productivity growth threaten employment?”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Bénassy-Quéré, A. (2017), “Making the European semester more efficient”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Bernanke, B. (2017), “When growth is not enough”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Bils, M., Klenow, P. and Ruane, C. (2017), Misallocation or mismeasurement, mimeo, Stanford University, 19 June.

Bloom, N., Jones, C., Van Reenen, J. and Webb, M. (2017), Are ideas getting harder to find?, mimeo, Stanford University, 11 July.

Buti, M. (2017), “Fiscal consolidation and reforms: trade-offs and complementarities”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Byrne, D., Fernald, J. and Reinsdorf, M. (2016), “Does the United States have a productivity slowdown or a measurement problem?”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 47(1), pp. 109-182.

Constâncio, V., Hartmann, P. and Tristani, O. (2015), Selected takeaways from the ECB’s Sintra Forum on “Inflation and Unemployment in Europe”, VoxEU, 28 October.

Döttling, R., Ladika, T. and Perotti, E. (2017a), The (self-)funding of intangibles, mimeo, 12 May, available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2863267.

Döttling, R., Gutiérrez, G. and Philippon, T. (2017b), “Is there an investment gap in advanced economies? If so, why?”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Draghi, M. (2014), “Unemployment in the euro area”, speech at the Annual Central Bank Symposium in Jackson Hole.

Eberly, J. (2017), Comment on “Is there an investment gap in advanced economies? If so, why?” by Robin Döttling, German Gutiérrez and Thomas Philippon, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Eggertsson, G. (2017), Comment on “Sources and mechanisms of impaired growth in advanced economies” by Robert Hall, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Garga, V. and Singh, S. (2016), Output hysteresis and optimal monetary policy, mimeo, Brown University, 11 November.

Gopinath, G., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Karabarbounis, L. and Villegas-Sanchez, C. (2017), “Capital Allocation and Productivity in South Europe”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

Gordon, R. (2016), The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War, Princeton University Press.

Guriev, S. (2017), “Impact of cycle on growth: human capital, political economy, and non-performing loans”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Gutiérrez, G., and Philippon, T. (2016), “Investment-less growth: an empirical investigation”, NBER Working Paper 22897, December.

Hall, R. (2017), “Sources and mechanisms of impaired growth in advanced economies”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Harhoff, D. (2017), Comment on “Robocalypse now: does productivity growth threaten employment?” by David Autor and Anna Salomons, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Johnson, S. (2017), “Increasing public support for research and development in the U.S.”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Jones, C. (2017), “A discussion: long term growth in advanced economies”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Karabarbounis, L., and Neiman, B. (2014), “The global decline of the labor share”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(1), pp. 61-103.

Mazzucato, M., and Semieniuk, G. (2017), “Public financing of innovation: from market fixing to mission oriented shaping”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Milanovic, B. (2016), Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, Harvard University Press.

Mokyr, J. (2017), “Is technical progress obsolete?”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2015), The Future of Productivity, Paris.

Schmidt, M. (2017), “Building an innovation ecosystem: lessons learned and a view to the future from MIT and Kendall Square”, lunch speech held at the ECB Forum on Central Banking on Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Sintra, 27 June, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cbZHjiWQ_iA.

Solow, R. (1956), “A contribution to the theory of economic growth”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 70(1), pp. 65–94.

Solow, R. (1957), “Technical change and the aggregate production function”, Review of Economics and Statistics 39(3), pp. 312-320.

Syverson, C. (2017), “Challenges to mismeasurement explanations for the US productivity slowdown”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(2), pp. 165-186.

Tobin, J. (1969), “A general equilibrium approach to monetary theory”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 1(1), pp. 15-29.

Varian, H. (2017), “Technology, innovation and industrial organization”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Veugelers, R. (2017), “An innovation deficit behind Europe’s overall productivity slowdown?”, forthcoming in ECB, Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies, Frankfurt am Main.

Ευρωπαϊκή Κεντρική Τράπεζα

Γενική Διεύθυνση Επικοινωνίας

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Η αναπαραγωγή επιτρέπεται εφόσον γίνεται αναφορά στην πηγή.

Εκπρόσωποι Τύπου