The impact of the recent spike in uncertainty on economic activity in the euro area

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 6/2020.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has triggered an unprecedented increase in uncertainty. Substantial uncertainty surrounds all aspects of the pandemic: the infectiousness and lethality of the virus; the capability of healthcare systems to adapt to a surge in demand and to develop a medical solution; the duration and effectiveness of containment measures (such as lockdowns and social distancing) and their impact on economic activity and employment; the speed of the recovery once containment measures are eased; and the extent to which the pandemic will permanently impact consumption, investment and growth potential.

This box shows how uncertainty has evolved in the euro area and the impact it will likely have on real economic activity. While uncertainty is not directly observable, a number of proxies have been proposed and applied in the literature.[1] This box shows how selected measures of uncertainty have evolved during the past few months and exploits the information embedded in a measure of macroeconomic uncertainty to assess its impact on economic activity. This is done using a Bayesian vector autoregressive (BVAR) model which allows us to estimate the dynamic effect of an uncertainty shock on the variable of interest.

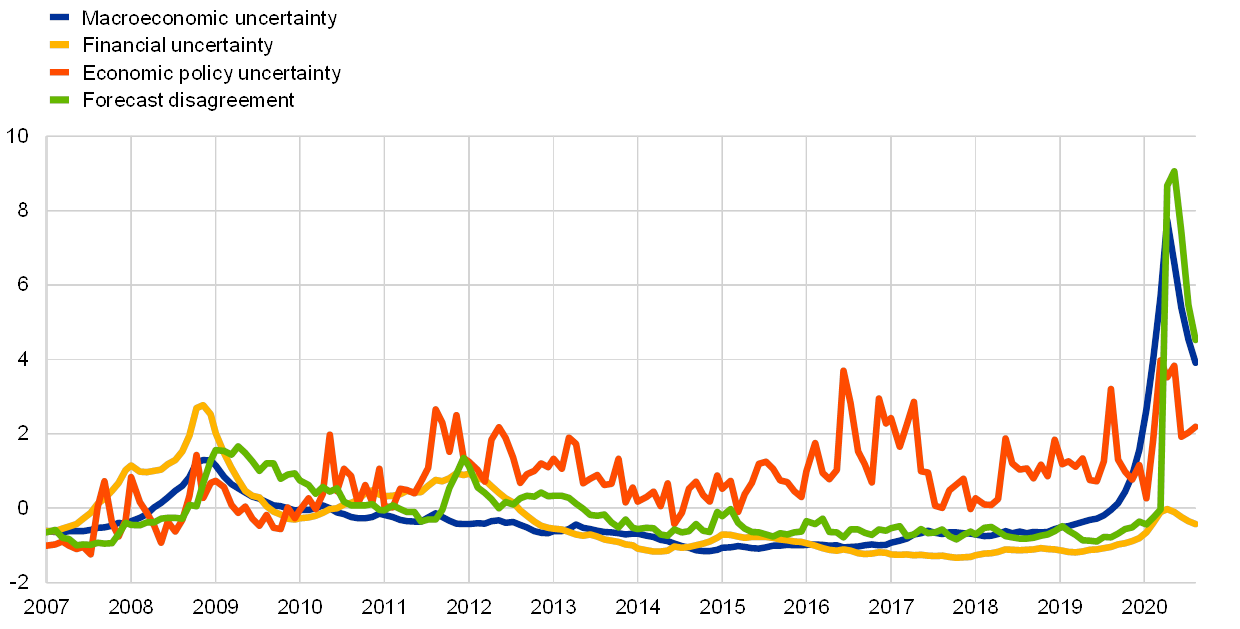

Selected measures confirm a steep increase in uncertainty coinciding with the spread of COVID-19 in the euro area. Chart A shows how four selected measures of uncertainty in the euro area have evolved over the past 13 years. The analysis includes two measures of macroeconomic and financial uncertainty. They are based on the difficulty of predicting future economic outcomes, which is a function of the increase in the projection errors for a broad range of business cycle and financial variables.[2] In addition, the analysis includes a widely used proxy of forecast uncertainty, measured through the disagreement among professional forecasters[3], and a measure of economic policy uncertainty which is based on newspaper coverage[4]. The chart shows that macroeconomic uncertainty, forecast disagreement and economic policy uncertainty have increased to historically high levels since early 2020, while financial uncertainty has increased more modestly. While the increase in financial uncertainty is likely to reflect an exogenous increase in uncertainty, the rather strong increase of the former group of uncertainty measures is likely to partly reflect an endogenous response of these measures to business cycle fluctuations.[5] In the current context, the imposition of lockdown measures led to hard-to-predict variations in macroeconomic variables and is thus responsible for at least part of the increase in these uncertainty measures. All this suggests that most of the observed increase in uncertainty can likely be attributed to the COVID-19 outbreak, which started to affect the euro area in February 2020.

Chart A

Measures of uncertainty in the euro area

(standard deviation from mean)

Sources: Eurostat, Haver and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: All measures of uncertainty are standardised to mean zero and unit standard deviation over the full horizon starting in June 1991. A value of 2 should be read as meaning that the uncertainty measure exceeds its historical average level by two standard deviations. The latest observations are for August 2020.

Heightened uncertainty is likely to dampen activity via a number of channels.[6] First, as investment and employment decisions may be costly to revert or even irreversible, it might be preferable for a company to postpone a decision until further information has become available or uncertainty about the future economic outlook has diminished. Second, high uncertainty may dampen activity through increasing risk premia and the rising costs of debt financing, as reduced predictability is generally associated with higher risk aversion. Third, high uncertainty could lead households to increase their precautionary savings, which would reduce current private consumption and further dampen GDP growth. Fourth, episodes of very high uncertainty might cause permanent changes in the behaviour of households and businesses, especially if they occur frequently. Finally, and given the above-mentioned channels, high uncertainty could make an economy less sensitive to monetary and fiscal policy actions; at the same time, if uncertainty is high, economic policy can be particularly effective by reducing uncertainty through several of the above-mentioned channels.

Model-based analysis suggests that uncertainty shocks have a substantial impact on real economic activity in the euro area. The BVAR model includes a set of monetary, real and nominal variables, as well as oil prices and a confidence indicator.[7] The measure of macroeconomic uncertainty discussed above is used as a proxy for uncertainty in the euro area. It is included as the first, and most exogenous, variable in the model, which implies that the estimated impact can be regarded as the upper end of the possible range.[8] The model is estimated over the period from the second quarter of 1991 to the second quarter of 2020 using quarterly data, with four lags.[9] The model is then used to simulate the dynamic effects of an uncertainty shock on the euro area economy.[10]

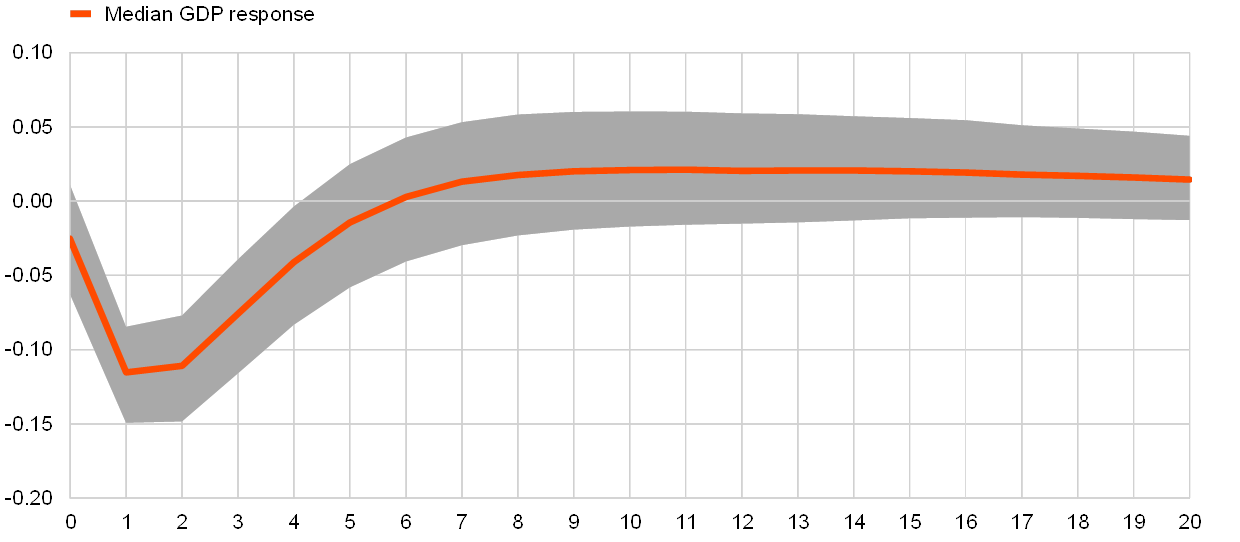

An adverse macroeconomic uncertainty shock has a significant negative effect on real GDP in the euro area in the short term (see Chart B). Following an increase in macroeconomic uncertainty by one standard deviation, real GDP growth is adversely affected for up to four quarters. The biggest impact is observed in the first and second quarters after the shock occurs, when the dent in real GDP growth amounts to 0.1 percentage points in each quarter. The cumulated impact on the level of real GDP one year after the shock is estimated to amount to around 0.4%. Afterwards, the significance of the impact diminishes. As is to be expected, real fixed capital formation reacts much more strongly to an increase in uncertainty (down about 0.7% six quarters after the shock) than real GDP, while real private consumption is less affected than GDP (down 0.2% one year after the shock). In the context of the model, a shock to uncertainty causes an immediate and substantial decline in economic sentiment and has a lasting impact on employment, which would decline by about 0.2% after two years.[11]

Chart B

Response of real GDP growth to a macroeconomic uncertainty shock of one standard deviation

(x-axis: quarters following the uncertainty shock; y-axis: percentage points)

Source: ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Impulse response of real GDP growth to a macroeconomic uncertainty shock of one standard deviation derived from the estimation of an 11-variable BVAR using quarterly data over the period from the second quarter of 1991 to the second quarter of 2020. The solid line is the median response and the range shows the 68% standard error bands.

The spike in macroeconomic uncertainty is likely to have contributed significantly to the decline in euro area real GDP in the first half of 2020. Most measures of uncertainty increased very sharply during this period, and the estimated impulse response functions suggest that the biggest impact of an uncertainty shock occurs shortly after the shock and in the following quarter. Against this background, heightened uncertainty is estimated to have accounted for around one-fifth of the decline in activity in the first half of 2020, notably in the second quarter, with a particularly strong impact on fixed capital formation.

Looking ahead, heightened uncertainty is likely to persist for some time and might therefore continue to dampen euro area real GDP growth during the next few quarters. The observed measures of uncertainty remained at highly elevated levels in July and August 2020, and they will likely remain elevated in the near term, at least until an effective medical solution to the COVID-19 pandemic has been found. Moreover, the impulse response functions shown in Chart B suggest that uncertainty shocks may dampen real GDP growth for up to four quarters. All this implies that, while economic activity is expected to recover over the next few quarters, uncertainty might continue to dampen the speed and momentum of the rebound in the near term. The BVAR model used for this exercise suggests that the current uncertainty shock will fade away only gradually and could dampen the expected rebound in activity by a cumulative 5% until mid-2021.[12] Should heightened uncertainty persist for a longer period, it could also imply an adverse impact for the longer-term growth potential.

- For an overview, see the article entitled “The impact of uncertainty on activity in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, ECB, 2016.

- See Jurado, K., Ludvigson, S.C. and Ng, S., “Measuring Uncertainty”, American Economic Review, Vol. 105, No 3, 2015, pp. 1177-1216.

- See, for example, Zarnowitz, V. and Lambros, L.A., “Consensus and Uncertainty in Economic Prediction”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 95, No 3, 1987, pp. 591-621.

- See Baker, S.R., Bloom, N. and Davis, S.J., “Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 131, No 4, 2016, pp. 1593-1636; and the box entitled “Sources of economic policy uncertainty in the euro area: a machine learning approach”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5, ECB, 2019.

- See Ludvigson, S.C., Ma, S. and Ng, S., “Uncertainty and Business Cycles: Exogenous Impulse or Endogenous Response?”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, forthcoming.

- For an overview, see Bloom, N., “Fluctuations in Uncertainty”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 28, No 2, 2014, pp. 153-176.

- The BVAR model includes 11 variables with the following ordering: (1) the macroeconomic uncertainty proxy, (2) the EURO STOXX 50 index, (3) the European economic sentiment indicator, (4) the USD/EUR exchange rate, (5) the long-term interest rate, (6) the oil price in EUR/barrel, (7) the GDP deflator, (8) total employment, (9) real private consumption, (10) real total fixed investment, and (11) real GDP. This ordering is based on the assumptions that financial markets and monetary variables are fast-moving, whereas real macroeconomic aggregates are comparatively slower-moving.

- A robustness analysis in which uncertainty is ordered last, and thus is the most endogenous variable, broadly confirms the results presented below.

- The BVAR methodology used in this analysis follows Lenza, M. and Primiceri, G.E., “How to estimate a VAR after March 2020”, Working Paper Series, No 2461, ECB, August 2020.

A Cholesky decomposition is applied on the variance-covariance matrix of the residuals to recover orthogonal shocks. - The adverse macroeconomic uncertainty shock corresponds to an increase in the respective shock series of one standard deviation.

- The impulse response functions suggest that an increase in financial uncertainty (ordered first in the BVAR) has a broadly comparable impact on activity.

- This is broadly comparable to recent estimates for the United States. See Baker, S.R., Bloom, N., Davis, S.J. and Terry, S.J., “COVID-Induced Economic Uncertainty”, NBER Working Paper Series, No 26983, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.