- 14 OCTOBER 2021

- RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 88

Low rates and bank stability: the risk of a tipping point

Policy rates in advanced economies are unusually low. What effect does this have on bank stability? I identify two competing effects. On the one hand, low rates harm bank profits by squeezing interest margins. On the other hand, they boost the value of long-term assets held by banks. Using a standard banking model, I determine the policy rate level at which these two forces cancel each other out, i.e. the tipping point. Past this tipping point, the net effect of low rates on bank capital is negative. Applying the model to the US economy, I quantify the tipping point in August 2007 as a policy rate of 0.55%.

Introduction: the economic implications of low rates

Since the global financial crisis, advanced economies have experienced unusually low interest rate levels. This has spurred academic and policy discussions about the economic implications of such low rates for the banking sector.[2]

The discussions have focused mainly on the effects on bank lending. Evidence has shown that low rates make banks lend to riskier counterparts (Dell’Ariccia, Laeven and Suarez, 2017; Heider, Saidi and Schepens, 2019), and that low rates may reduce the overall quantity of lending (Brunnermeier and Koby, 2018; Repullo, 2020).

When is bank solvency affected? A model to identify the tipping point

The research I present in this article, developed fully in Porcellacchia (2021), studies the effect of low rates on bank solvency and hence on the probability of a crisis. It develops a model closely based on Allen and Gale (1998) and shows the existence of a critical policy rate level, dubbed the tipping point.

Past the tipping point, an interest rate cut has a negative net effect on bank capital and may indeed result in bank insolvency. From the model, we learn which bank characteristics matter for the tipping point and how they affect it. Using these theoretical results, we can use data on banks to quantify the tipping point.

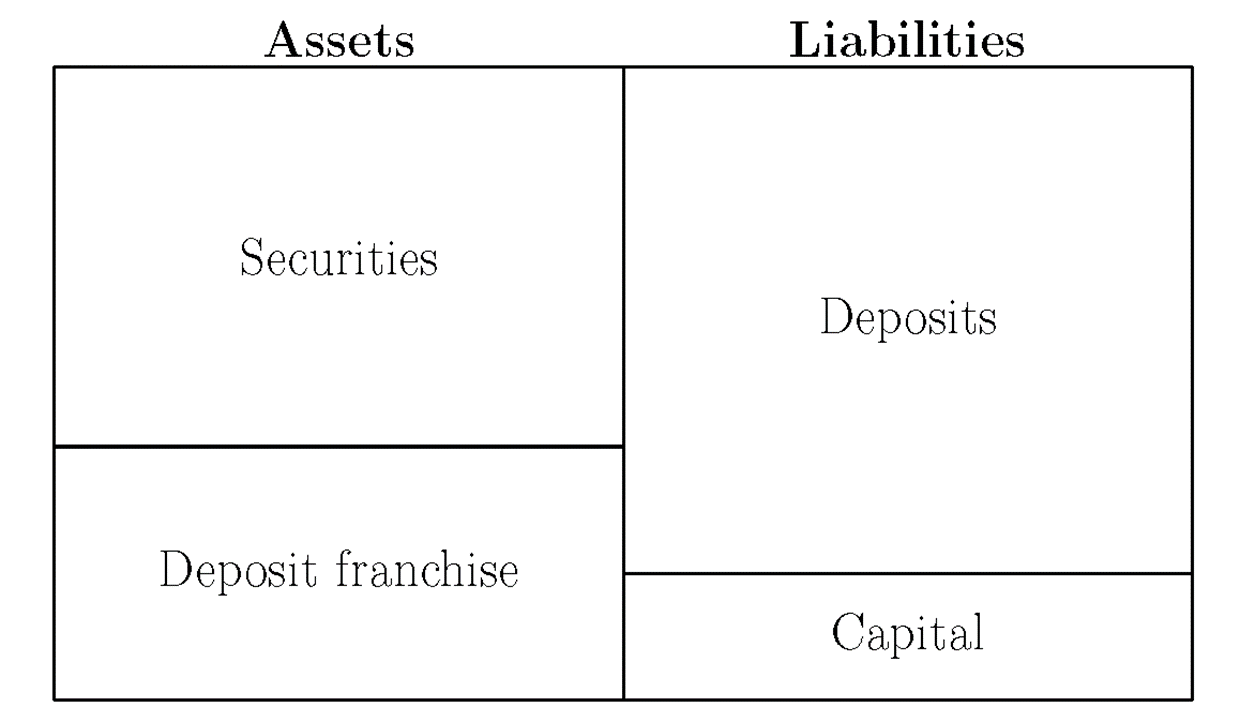

Conceptual framework: the deposit franchise as a bank asset

To discuss bank solvency, we need to understand what constitutes the assets of a bank from an economic point of view. In this respect, the model makes clear that we should not only think of bank assets according to accounting standards (e.g. loans, bond holdings, etc.). A bank’s deposit franchise, which is generally not capitalised on bank balance sheets, is also a relevant bank asset.[3] The deposit franchise is the value for a bank of having a deposit base on which it earns an interest margin. Chart 1 summarises this view in an “economic” bank balance sheet.

Chart 1

A stylised “economic” bank balance sheet

In this framework, a bank is solvent as long as its assets, which include its deposit franchise, are enough to cover its deposits. If not, a crisis is precipitated by deposit withdrawals. With this concept of solvency in mind, the question becomes: what is the effect of a low policy rate on bank assets?

Effects of the policy rate on bank assets

A reduction in the policy rate has two competing effects on bank assets. First, there is a revaluation effect. Bank loans and other securities held by banks are typically long-term. This means that, when the policy rate falls, the interest rate those assets earn does not. Hence, these assets appreciate in value. This effect strengthens bank solvency. Second, an erosion of the deposit franchise occurs. As the policy rate falls, banks’ interest margins become thinner, since cash increasingly becomes a better outside option for depositors. This effect weakens bank solvency.

At normal values of the interest rate, the revaluation effect dominates. That is, a small policy rate cut bolsters bank solvency. However, the further the policy rate falls, the larger the adverse effect on the deposit franchise becomes. At the tipping point, the two effects cancel each other out. Past the tipping point, the deposit-franchise effect dominates and a policy rate cut hurts bank solvency.

Key variables to quantify the tipping point

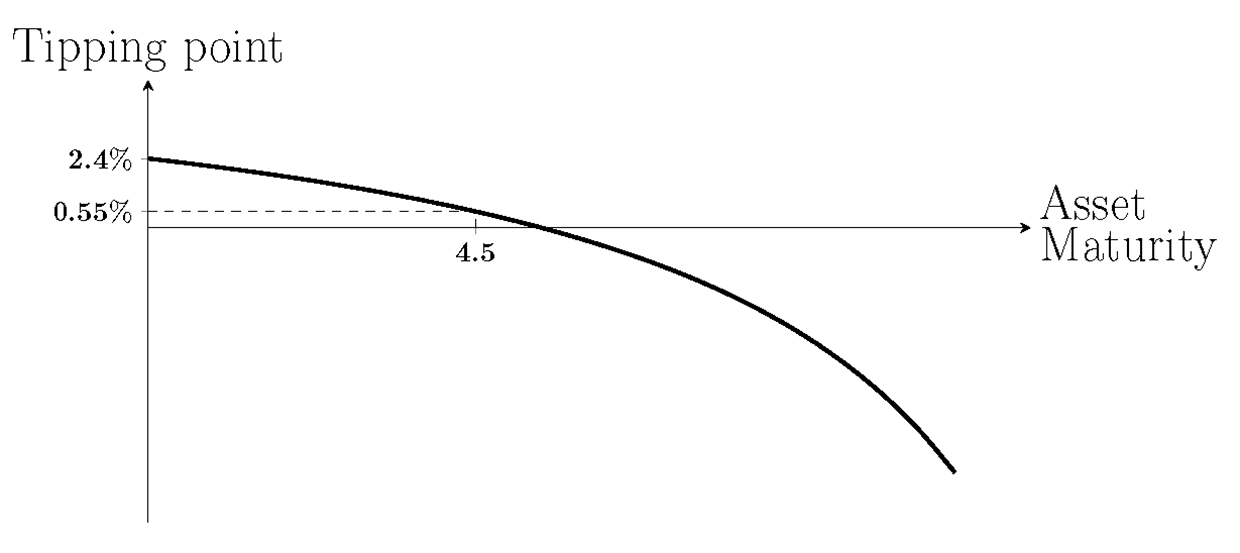

Quantification of the model’s tipping point is possible with just a few observable bank characteristics. The key variable in quantifying the deposit-franchise effect is banks’ interest margin. The key variable for the revaluation effect is the average time to maturity of bank loans and other securities held by banks. In August 2007 in the United States, on average these two variables stood respectively at 2.4% and 4.5 years.

Chart 2 plots the tipping point as a function of the time to maturity of bank-held securities. Banks are more resilient to low rates when they hold longer-term securities. In fact, if banks held exclusively overnight securities such as bank reserves, then there would be no revaluation effect and the tipping point would correspond to the bank’s interest margin. A stronger revaluation effect pushes the tipping point down. Our observed value for average bank asset maturity (4.5 years) implies that a 0.55% policy rate is the tipping point.

Chart 2

Quantified tipping point

On the horizontal axis is the average time to maturity of bank-held securities expressed in years. On the vertical axis is the tipping point. The graph is parametrised with an interest margin of 2.4%, an initial policy rate of 5% and a per-unit deposit franchise of 20%.

The main purpose of this quantification is to illustrate the properties of the model. The purpose is not to estimate a tipping point, valid at different points in time or for different economies. Indeed, it would be wrong to attribute the value of 0.55% to the euro area or the United States today. Their economic fundamentals are different from those of the US economy before the global financial crisis. Moreover, the state of the banking system in these economies has changed profoundly since 2007, as banks have had time to transition to the new economic environment.

Conclusion

This research shows that very loose monetary policy can have an adverse impact on the health of the financial system. It proposes the tipping point as a model-based indicator, which summarises information about the banking sector and marks the policy rate level at which concerns about financial stability are warranted. In the region past the tipping point, the benefits of monetary easing should be more carefully weighed against the costs to financial stability.[4]

More work is required to obtain a sound quantification of the tipping point, also for the euro area. As it stands, the model is highly stylised. By design, its elements are easily mapped into empirical counterparts to make quantification possible. However, many important bank characteristics, such as capital regulation, find no place in the model. Also, interest rate dynamics are overly simplified with the assumption of a flat yield curve.

References

Allen, F. and Gale, D. (1998), “Optimal Financial Crises”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 53, No 4, August, pp. 1245-1284.

Altavilla, C., Burlon, L., Giannetti, M. and Holton, S. (2021), “Is There a Zero Lower Bound? The Effects of Negative Policy Rates on Banks and Firms”, Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming.

Brunnermeier, M. and Koby, Y. (2019), “The Reversal Interest Rate”, mimeo.

Dell’Ariccia, G., Laeven, L. and Suarez, G. (2017), “Bank Leverage and Monetary Policy's Risk-Taking Channel: Evidence from the United States”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 72, No 2, April, pp. 613-654.

Drechsler, I., Savov, A. and Schnabl, P. (2021), “Banking on Deposits: Maturity Transformation without Interest Rate Risk”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 76, No 3, June, pp. 1091-1143.

Heider, F. and Leonello, A. (2021), “Monetary Policy in a Low Interest Rate Environment: Reversal Rate and Risk-Taking”, Working Paper Series, No 2593, ECB, October.

Heider, F., Saidi, F. and Schepens, G. (2019), “Life below Zero: Bank Lending under Negative Policy Rates”, Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 32, No 10, October, pp. 3728-3761.

Porcellacchia, D. (2020), “What is the tipping point? Low rates and Financial Stability”, Working Paper Series, No 2447, ECB, July.

Porcellacchia, D. (2021), “The Tipping Point: Low Rates and Financial Stability”, mimeo.

Repullo, R. (2020), “The Reversal Interest Rate. A Critical Review”, CEMFI Working Paper, No 2021, October.

- Disclaimer: The article was written by Davide Porcellacchia (Directorate General Research, European Central Bank). The author thanks Michael Ehrmann, Philipp Hartmann, Luc Laeven, Alexander Popov and Louise Sagar. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem.

- An overview is given in Heider and Leonello (2021).

- Recent evidence of the importance of the deposit franchise for banks can be found in Drechsler, Savov and Schnabl (2021).

- Altavilla et al. (2021) find beneficial macroeconomic effects of monetary easing at low and even negative levels of the interest rate.