- THE ECB BLOG

Welcoming Croatia to the family: what’s changed at the ECB?

19 April 2023

Croatia officially joined the euro area on 1 January. A previous blog post discussed the many changes this heralded for the country. But the new arrival also changed certain aspects of how things work at the ECB, as shown in this ECB Blog post.

When a country adopts the euro, there is always extensive coverage of the economic implications of adopting a new currency. Consumers can travel without exchanging money, businesses can trade more easily in the Single Market, and people might argue about whether the change triggers extra inflation (not really, it turns out). But of course, the change has also substantial effects on the monetary union. When someone joins the family, and gets a seat around the table, some things change or need to be rearranged. Here we focus on the capital of the ECB and voting rights in the Governing Council.

How does Croatia’s accession affect the ECB’s capital?

The ECB has its own capital to operate and safeguard its financial independence from political influence. It is exclusively subscribed by the national central banks (NCBs) of the European Union (EU) as the ECB’s sole shareholders.

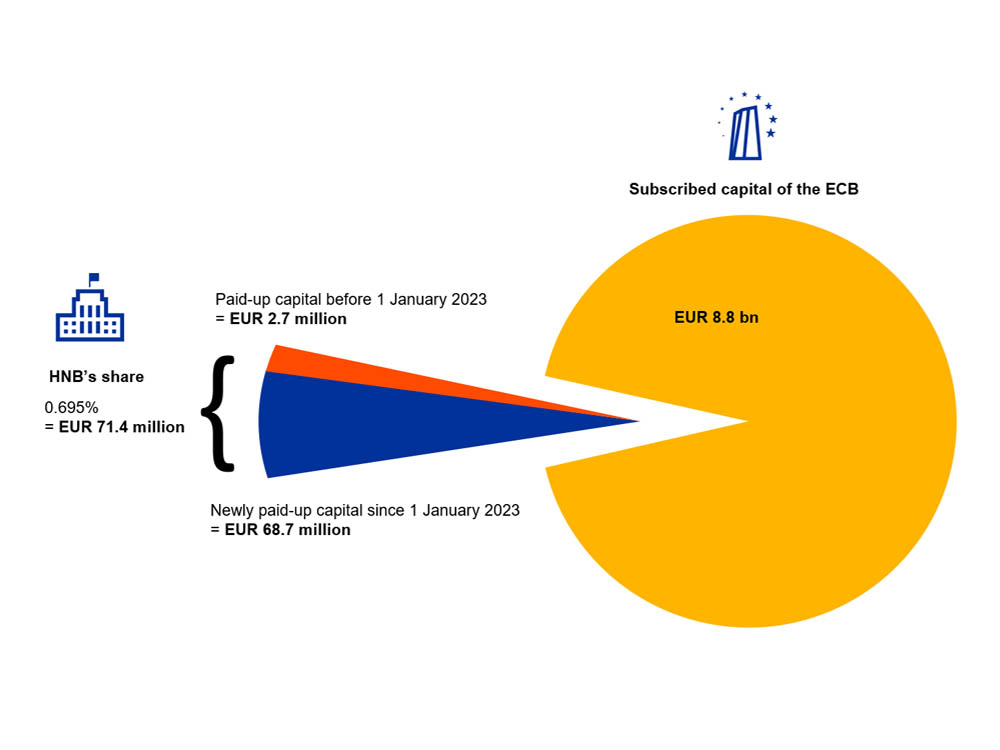

The ECB’s total subscribed capital of €10.8 billion is divided between all of the NCBs of the EU. Each NCB’s share is calculated using the ECB’s capital key, which is based on the respective Member State’s share in the total population and gross domestic product of the EU. [1] Under this key, Hrvatska Narodna Banka’s (HNB) share of the total is 0.6595%, corresponding to €71,390,921. This was true even before the country’s adoption of the euro on 1 January 2023.

What did change on that date, however, is the amount of the subscribed capital that HNB actually paid up to the ECB. That’s because the NCB of every EU Member State that has not joined the euro area yet is required to pay up just 3.75% of its subscribed capital as a contribution to the ECB’s operational costs.[2] Before joining the Eurosystem, Croatia had already paid up just under €2.7 million.

Upon joining the euro area, HNB was thus required to pay the remaining 96.25% of its subscribed capital according to the capital key. This remaining amount corresponds to €68.7 million.[3] As a result, HNB’s entry into the Eurosystem increased the total amount of the ECB’s paid-up capital to €8.9 billion. That is the total subscribed capital minus the amounts that the seven NCBs of EU member states that currently remain outside the Eurosystem don’t have to pay up.

In addition to paying up the total amount of their share in the ECB’s subscribed capital as described above, euro area NCBs also transfer foreign reserve assets when joining the Eurosystem.[4]

After Croatia joined the euro area, HNB transferred foreign reserve assets, i.e. dollar, yen, and other currencies, to the ECB in proportion to its subscribed capital, with a total value of almost €640 million. HNB was credited with claims in respect of the paid-up capital and foreign reserve assets equivalent to the amounts transferred.

And what about how the ECB reaches its decisions?

Even before Croatia adopted the euro, HNB Governor Boris Vujčić attended meetings of the General Council of the ECB, which deals with matters relating to euro adoption, as was his right as the head of the NCB of a non-euro area EU Member State. Now that Croatia is part of the euro area, however, Governor Vujčić is a full member of the Governing Council, the ECB’s top decision-making body that is responsible for defining the central bank’s monetary policy. The Governing Council comprises the six Executive Board members alongside the (now) 20 governors of the national central banks of the euro area member countries. This growing number of members is where things become a bit complicated, because not all governors have voting rights all the time. But why is that?

As the Economic and Monetary Union grew over time, and with it the Eurosystem, it became important to figure out how to keep decision-making processes manageable so that crucial decisions could be reached in as timely a manner as possible. For that purpose the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the European Central Bank, which sets out how the ECB functions, limits the number of voting Governing Council members to 21 as soon as the number of NCB governors represented exceeds 18.[5] When Lithuania became the 19th country to join the euro area, in 2015, this threshold was reached and a new system of rotating voting rights was implemented.[6] The six board members have a right to vote at all Governing Council meetings.[7] All other member of the Governing Council – the 20 governors – share the remaining 15 votes on a rotating basis and have to forego their voting rights once in a while.

Some governors hold their voting rights less often than others. In order to take into account the relative sizes and economic weights of their home countries and the importance of their financial centres, the governors are split into two groups. The governors from countries ranked first to fifth (currently Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands) share four votes, which means that each of them forgoes voting rights every five months. The remaining governors share the other 11 votes. Within this second group, the participation of the Governor of HNB means that the 11 voting rights are now shared by 15 NCB heads, which increases the frequency with which each governor temporarily foregoes their right to vote. Currently four governors have to forego their right to vote each month.[8]

Both groups exercise their votes on a randomised monthly rotating basis (overview of the full schedule).[9]

In any case, all Governing Council members remain entitled to attend all meetings, receive all documentation and exercise the right to speak, in accordance with the principle of participation. The system of voting rights is designed to ensure that decisions are reached in a timely manner, and by a simple majority. In practice, however, the Governing Council actually reaches a consensus on most issues.

In a nutshell

So, while the attention during any new arrival into the euro area is on the effects on the individual country, there are also always changes to how things work in the background. The capital (and therefore the ownership structure) of the ECB changes every time, and the voting system by which the central bank reaches its decisions is adjusted to accommodate the new member. Every time the euro family gets bigger, the ECB evolves too.

For more information have a look at the relevant section on the ECB's website.

Decision (EU) 2020/138 of the European Central Bank of 22 January 2020 on the paying-up of the European Central Bank’s capital by the national central banks of Member States whose currency is the euro and repealing Decision (EU) 2019/44 (ECB/2020/4) and Decision (EU) 2020/136 of the European Central Bank of 22 January 2020 on the paying-up of the European Central Bank’s capital by the non-euro area national central banks and repealing Decision (EU) 2019/48 (ECB/2020/2).

See Article 48(1) of the ESCB/ECB Statute providing that the NCB whose derogation is abrogated must pay up its share in the subscribed capital of the ECB in line with the central banks of other Member States whose currency is the euro.

ibid., providing that the NCB whose derogation is abrogated shall transfer to the ECB foreign reserve assets in line with Article 30.1 of the ESCB/ECB Statute.

See Article 10.2 of the ESCB/ECB Statute and Decision of the European Central Bank to postpone the start of the rotation system in the Governing Council of the European Central Bank of 18 December 2008 (ECB/2008/29).

ibid.

Except during votes relating to the capital of the ECB, the capital key, foreign reserve assets or the allocation of monetary income and profits and losses.

For more on the rotation system check out this explainer on the ECB’s website.

See Art. 3a.2 Decision of the European Central Bank of 19 February 2004 adopting the Rules of Procedure of the European Central Bank (ECB/2004/2) specifying that the rotation of voting rights starts at a random point in the list of the national central banks. This list follows the alphabetical order of to the names of the Member States in the national languages.