The European exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) as a preparatory phase on the path towards euro adoption – the cases of Bulgaria and Croatia

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 8/2020.

Following the completion of a roadmap agreed over the past few years among all relevant EU stakeholders, the Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna were included in the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) on 10 July 2020. Their inclusion marks a milestone towards future enlargement of the euro area, given the important role that ERM II plays as a preparatory phase for euro adoption. Participation in ERM II may lead to a regime shift in the country concerned, i.e. it may alter the incentives of international and local investors and of the national authorities.

We provide evidence that a regime shift indeed occurred in the central and eastern European countries (CEECs) that joined the mechanism in 2004 and 2005. If supported by sound economic policies, this shift may have positive consequences, such as accelerating the convergence process. Conversely, the implementation of ill-advised policy measures may contribute to a build-up of economic imbalances. The article also looks at ERM II from a historical perspective, reviews its main features and procedures and explains the new roadmap towards participation in ERM II – and, simultaneously, European banking union – that was established and successfully implemented for Bulgaria and Croatia.

The main conclusion of the article is that in order to fully reap the benefits of monetary integration and ensure their own smooth participation in the mechanism, countries need sound policies, governance and institutions which allow them to address risks with adequate macroeconomic, macroprudential, supervisory and structural measures.

1 Introduction

Two EU Member States, Bulgaria and Croatia, joined ERM II on 10 July 2020. The process began in 2017 along a roadmap that reflected lessons learned from other countries’ experiences, the advent of European banking union and a careful assessment of country-specific strengths and vulnerabilities.[1] The roadmap was agreed between the Bulgarian and Croatian authorities and the ERM II parties – the finance ministers of the euro area countries, the ECB, Denmark’s Finance Minister and the Governor of Danmarks Nationalbank.[2] These stakeholders took their decisions following a common procedure involving the European Commission and consultation of the Economic and Financial Committee in its euro area format, known as the Eurogroup Working Group (EWG).

The inclusion of the Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna in ERM II is a milestone towards further enlargement of the euro area. Bulgaria and Croatia are expected to adopt the euro once they have fulfilled the necessary requirements (the “Maastricht” convergence criteria) as assessed in the Convergence Reports of the European Commission and the ECB.[3]

For Bulgaria and Croatia, ERM II will therefore serve not only as an exchange rate arrangement, but also as a preparatory phase for euro adoption. ERM II has two main purposes. The first is to act as an arrangement for managing exchange rates between the participating currencies, thus also contributing to the smooth functioning of the single European market by fostering exchange rate stability. The second is to assist the convergence assessment provided for in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) with regard to the adoption of the euro by non-euro area EU Member States, with the exception of Denmark, which has a special status.[4] In this way, ERM II offers a testing ground before the adoption of the euro, as the economies of the participating Member States operate under a regime of stable exchange rates vis-à-vis the euro (market test) and are expected to further strengthen their macroeconomic, macroprudential, supervisory and structural policies (policy test), with the support of ever-evolving economic governance from the European Union.

This article looks at the participation of the Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna in ERM II, focusing on the mechanism’s role as a bridge from domestic currencies towards the euro. Specifically, Section 2 briefly reviews the history, main features and procedures of ERM II. Section 3 argues on the basis of quantitative evidence that ERM II may lead to a regime shift in participating countries on the path to euro adoption. Section 4 explains the roadmap towards ERM II participation that was established and implemented for Bulgaria and Croatia. Finally, Section 5 concludes by highlighting the way ahead and the key challenges faced by Bulgaria and Croatia on the path towards euro adoption.

2 The history, main features and procedures of ERM II

2.1 History

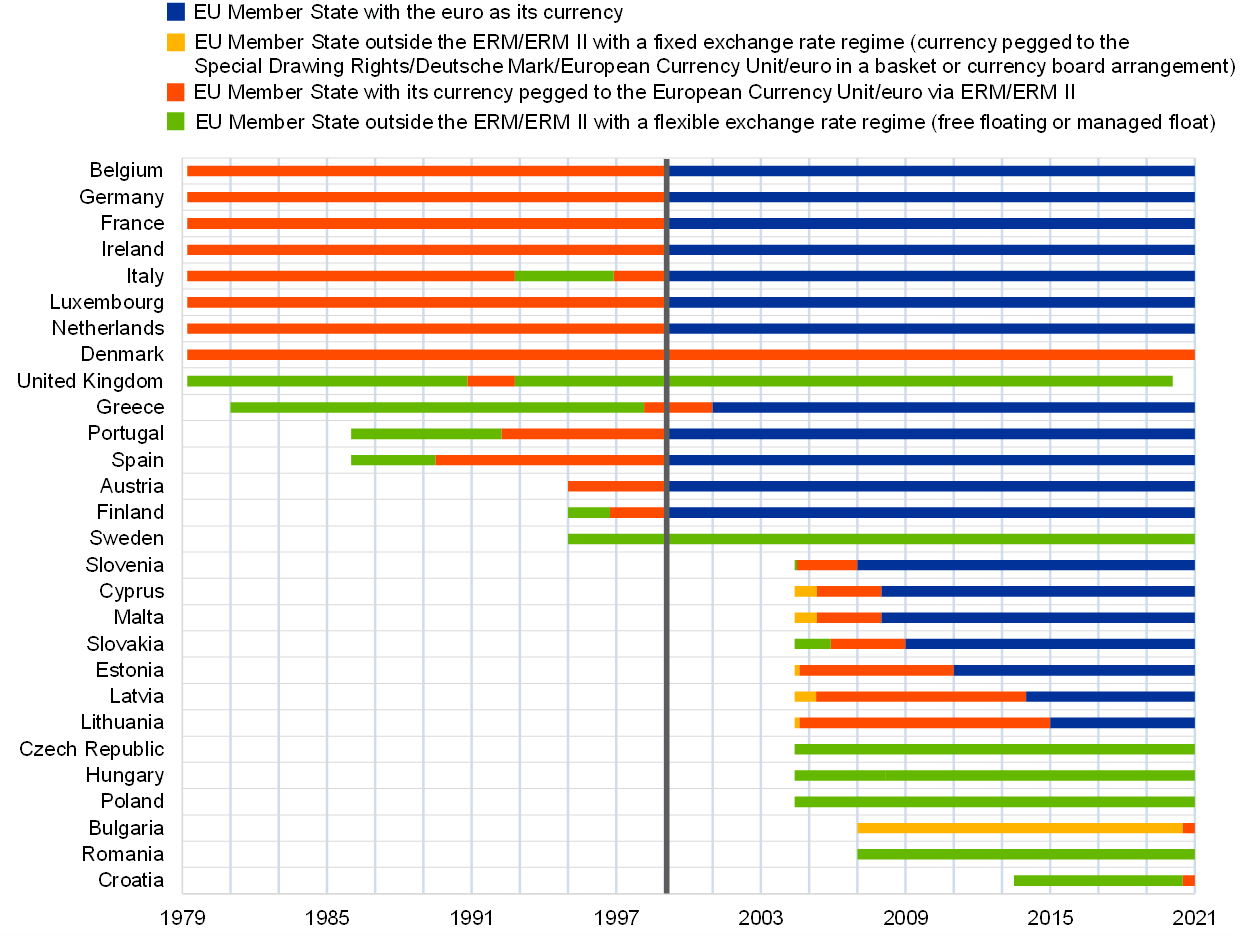

With the introduction of the euro on 1 January 1999, ERM II replaced the original exchange rate mechanism, which was one of the components of the European Monetary System (EMS) in place since 13 March 1979.[5] The original ERM, a core element of the EMS, was aimed at reducing exchange rate variability and fostering monetary stability among the currencies of an initial eight Member States. With the introduction of the euro, the Danish krone and the Greek drachma were included in the new mechanism, ERM II. After Greece adopted the euro in 2001, Denmark was the only non-euro area EU Member State participating in the mechanism until 2004 (see Chart 1).

Chart 1

Exchange rate regimes of EU Member States since the start of the European Monetary System

Source: ECB.

Notes:

1) The ERM, which was one element of the European Monetary System, became operational on 13 March 1979 and ended with the start of Stage Three of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) on 1 January 1999. On the same day the ERM was succeeded by ERM II.

2) Belgium and Luxembourg were in a monetary association until the adoption of the euro in 1999.

3) The standard fluctuation band around the central rates in the ERM was ± 2.25%, except for the Italian lira, the Spanish peseta, the Portuguese escudo and the UK pound sterling, for which it was ± 6%. From 8 January 1990 until 16 September 1992 the Italian lira (previously in the wide band of the ERM) was in the narrow band.

4) In August 1993 the ERM fluctuation band was widened temporarily to ± 15% for all ERM participants.

5) In September 1992 the participation of the Italian lira and the UK pound sterling in the ERM was suspended. The Italian lira resumed full participation in the ERM in November 1996.

6) Greece participated in ERM II in the period 1999-2000 with the new standard ±15% fluctuation band. Denmark kept the ± 2.25% fluctuation band within both the ERM and ERM II. While the nominal band was standard, nearly all subsequent ERM II members unilaterally committed to a narrower actual fluctuation band upon joining ERM II. These commitments do not involve any obligations on the part of the other ERM II parties.

7) The Czech Republic introduced a one-sided exchange rate floor towards the euro from November 2013 to April 2017.

8) The United Kingdom withdrew from the EU on 31 January 2020.

On 1 May 2004 ten new Member States joined the European Union and their national central banks (NCBs) became part of the ERM II Central Bank Agreement. On 28 June 2004, soon after EU enlargement, the Estonian kroon, the Lithuanian litas and the Slovenian tolar were added to ERM II. On 2 May 2005 the Cyprus pound, the Latvian lats and the Maltese lira joined the mechanism, followed by the Slovak koruna on 28 November 2005. Since then, all these countries have adopted the euro after “fulfilling their obligations regarding the achievement of economic and monetary union” (Article 140 of the TFEU), which included receiving positive convergence assessments from the ECB and the European Commission (see Chart 1).

2.2 Main features

ERM II was established by the European Council Resolution of 16 June 1997[6], which stipulated that “The euro will be the centre of the new mechanism.” The main features of ERM II are (i) a central rate against the euro, (ii) a fluctuation band with a standard width of ±15% around the central rate, (iii) interventions at the margins of the agreed fluctuation band, and (iv) the availability of very short-term financing from the participating central banks. Participating NCBs may unilaterally commit themselves to tighter fluctuation bands (including currency board regimes) than those provided for by ERM II, without imposing any additional obligations on the other participating NCBs or the ECB.[7] Interventions at the margins of the fluctuation bands are in principle automatic and unlimited, although the ECB and the participating NCBs can suspend them at any time if they conflict with the primary objective of maintaining price stability. During ERM II participation, realignments of the central rate or adjustments to the width of the fluctuation band may occur, for example if equilibrium exchange rates change over time. Such developments may take place not only during a process of real convergence, but also in the case of significant changes in external competitiveness or in the presence of inconsistent economic policies.

2.3 Main procedures

While ERM II is referred to in the Treaty as an integral part of the Maastricht exchange rate convergence criteria, the ERM II procedures and agreements are not based on the Treaty, since they are intergovernmental in nature. According to Article 2.3 of the European Council Resolution of 1997, the decisions regarding participation in ERM II – in particular, whether the currency of a country can be included in the mechanism with a certain central rate and fluctuation band – are taken by mutual agreement of the finance ministers of euro area countries, the ECB and the finance ministers and central bank governors of the non-euro area Member States participating in ERM II at any given time. The decisions are taken at the end of a process involving consultation of the EWG. The European Commission is also involved in this process; it participates in the relevant meetings, can be mandated particular tasks and is kept informed by the ERM II parties. As participation in ERM II is a precondition for the eventual introduction of the euro, all EU Member States with a derogation from the obligation to adopt the euro, i.e. all non-euro area Member States except Denmark, are expected to join the mechanism at some stage.

In the interests of all stakeholders, decisions regarding participation in ERM II are to be mutually agreed on the basis of a sound and thorough economic assessment conducted by the relevant parties, and in consultation with the European Commission, through a candid, in-depth exchange of views. The requirement for mutual agreement on ERM II participation means that there must be a consensus that the Member State concerned is pursuing effective stability-oriented policies consistent with smooth participation in the mechanism. All parties take part in the search for consensus in a positive spirit, and negotiations continue until there is an agreement acceptable to all. This is reflected in the policy position on ERM II adopted by the ECB’s Governing Council in 2003, which emphasises the need to take a holistic approach and to carry out a comprehensive analysis in the economic assessment.[8]

3 The “regime shift” effect of ERM II on investor and policymaker behaviour

3.1 Motivation

The full benefits of euro adoption can only be enjoyed if adequate policy measures are in place, including at the national level.[9] Attaining “a high degree of sustainable convergence” (Article 140 of the TFEU) is the most important precondition for the successful adoption of the euro. To this end, sound policies and an adequate level of institutional quality are of the essence. They are therefore given due consideration when assessing the readiness of a non-euro area EU Member State to participate in ERM II.

This is all the more important as participation in ERM II may affect the expectations and economic incentives of international and local investors, as well as those of the local policy authorities, in a regime shift that may in turn trigger various positive or negative dynamics. Progress in the process of monetary integration, as well as the prospect of adopting the euro, may improve international investor sentiment towards Member States joining ERM II. This may result in an acceleration of gross international financial inflows and, in turn, stronger domestic credit growth coupled with a significant improvement in financing conditions. While this may fuel a sustainable catching-up process, it may also provide the wrong sort of incentives if coupled with a weak institutional and business environment, potentially leading to misallocation of capital, postponement of necessary reforms and deterioration in the country’s adjustment capacity, for example. The ensuing build-up of imbalances might eventually exacerbate a possible international financial flow reversal.[10]

Against this backdrop, several insights can be gained from the analysis of developments in international financial flows and credit growth in the countries which have joined ERM II in the past. The analysis focuses on the CEECs that joined ERM II in 2004 and 2005 and subsequently adopted the euro: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia and Slovakia. Section 3.2 compares their experiences with those of the EU Member States in the same region which have not yet participated in ERM II (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania) or which joined the mechanism only very recently (Bulgaria and Croatia). Section 3.3 discusses some policy implications arising from this analysis.

3.2 Evidence

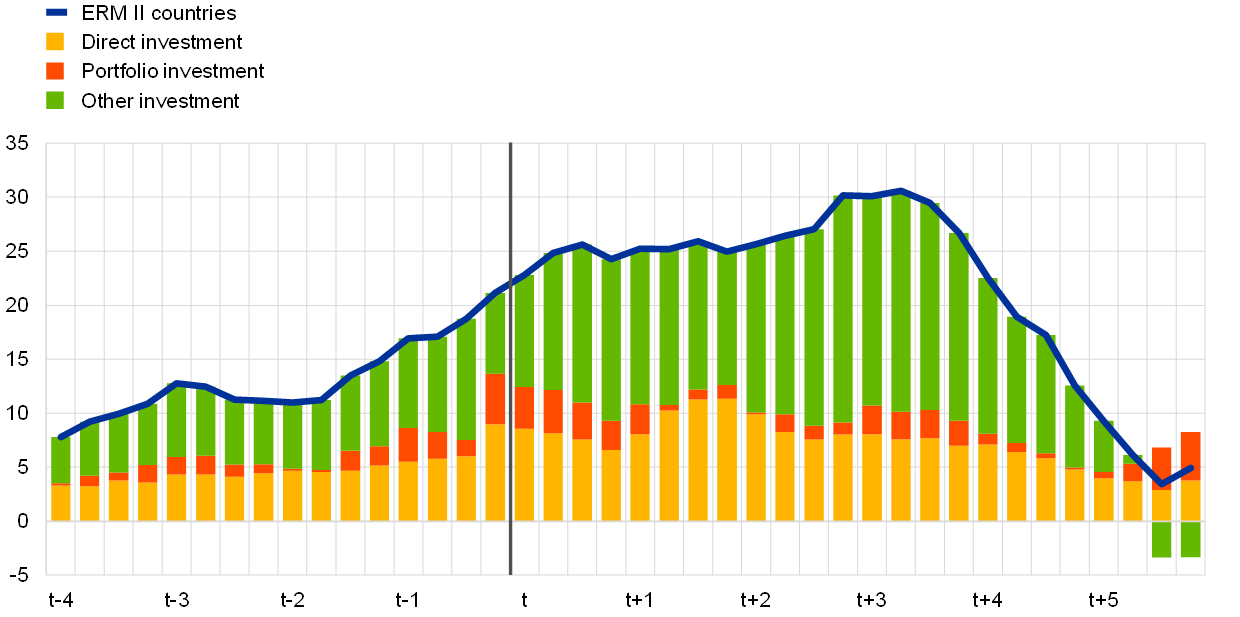

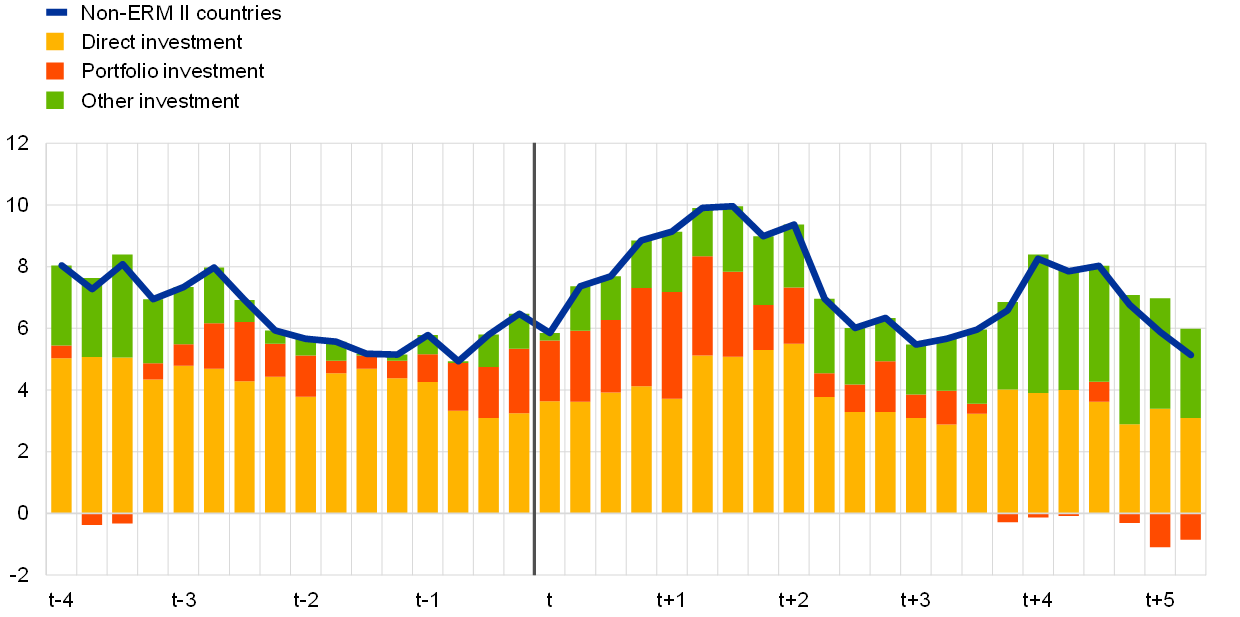

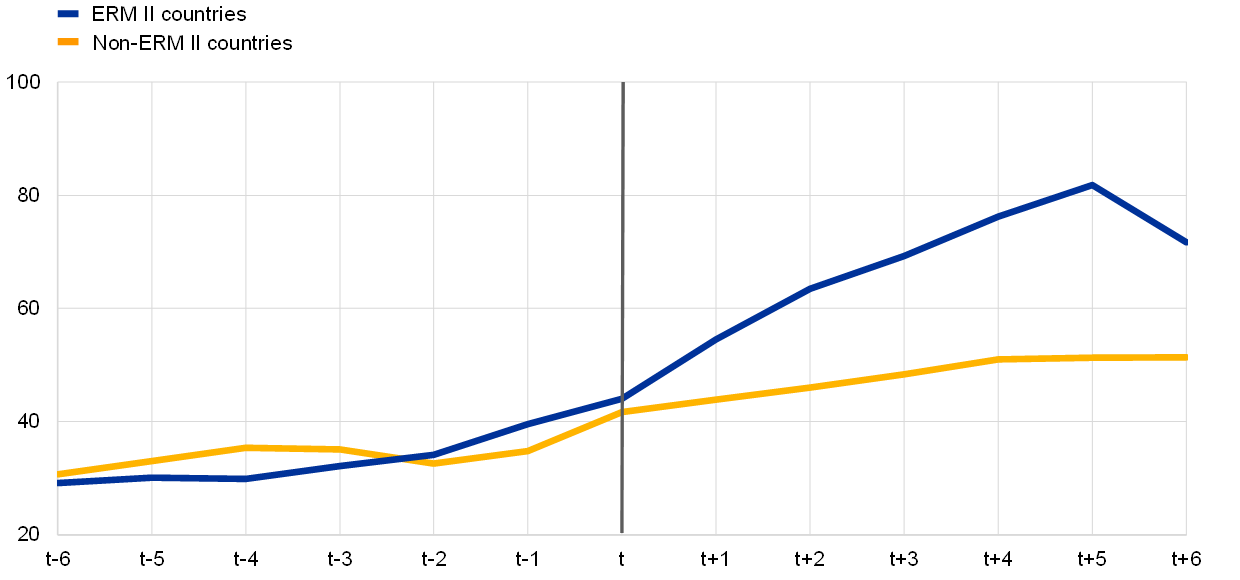

Following the accession of the above CEECs to the European Union, countries that participated in ERM II experienced a more pronounced international financial flow cycle than those which did not participate. Gross financial inflows as a share of GDP accelerated ahead of EU accession, which for some countries also coincided with the start of their participation in ERM II.[11] However, countries that joined ERM II experienced a much stronger surge (see Charts 2 and 3). Gross financial inflows in ERM II countries peaked about three years after they joined ERM II, at an average of around 30% of GDP (see Chart 2). Conversely, gross financial inflows were more stable in the non-ERM II countries, remaining at between 5% and 10% of GDP following EU accession (see Chart 3). With the onset of the global financial crisis in 2007-08, which materialised in most of the observed countries about three to four years after EU accession, ERM II participants experienced a sharper financial flow reversal (see Charts 2 and 3).[12] Supporting the quantitative evidence, internal econometric analysis on a sample of emerging market and (former) transition economies shows that the degree of flexibility of the exchange rate regime does not affect financial inflows to these countries, whereas ERM II participation is found to increase the magnitude of gross financial inflows. At the same time, the results suggest that EU accession is not relevant in explaining the financial inflows recorded.[13]

Chart 2

Gross international financial inflows of CEECs before and after joining ERM II

(as a percentage share of GDP; unweighted averages)

Source: ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The countries covered are Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia and Slovakia. Period “t” is a country-specific event and identifies the year in which the country joined ERM II: 2004 for Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia, and 2005 for Latvia and Slovakia.

Chart 3

Gross international financial inflows of CEECs not participating in ERM II before and after joining the European Union

(as a percentage share of GDP; unweighted averages)

Source: ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The countries covered are Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. Period “t” is a country-specific event and identifies the year of the country’s accession to the European Union: 2004 for the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, 2007 for Bulgaria and Romania, and 2013 for Croatia.

The differences in gross international financial inflows between the CEECs participating in ERM II and other CEECs were driven largely by bank lending and, to a lesser extent, by inward foreign direct investment (FDI). The largest share of financial flows to ERM II CEECs took the form of “other investment”, consisting mainly of bank lending to firms and households and flows within banking groups. While this may reflect the strong presence of foreign (mostly EU-based) banks in ERM II CEECs during that period, it was a common feature across the whole region. Conversely, the composition of international financial flows to non-ERM II CEECs was much more evenly distributed between FDI and other investment (see Charts 2 and 3).

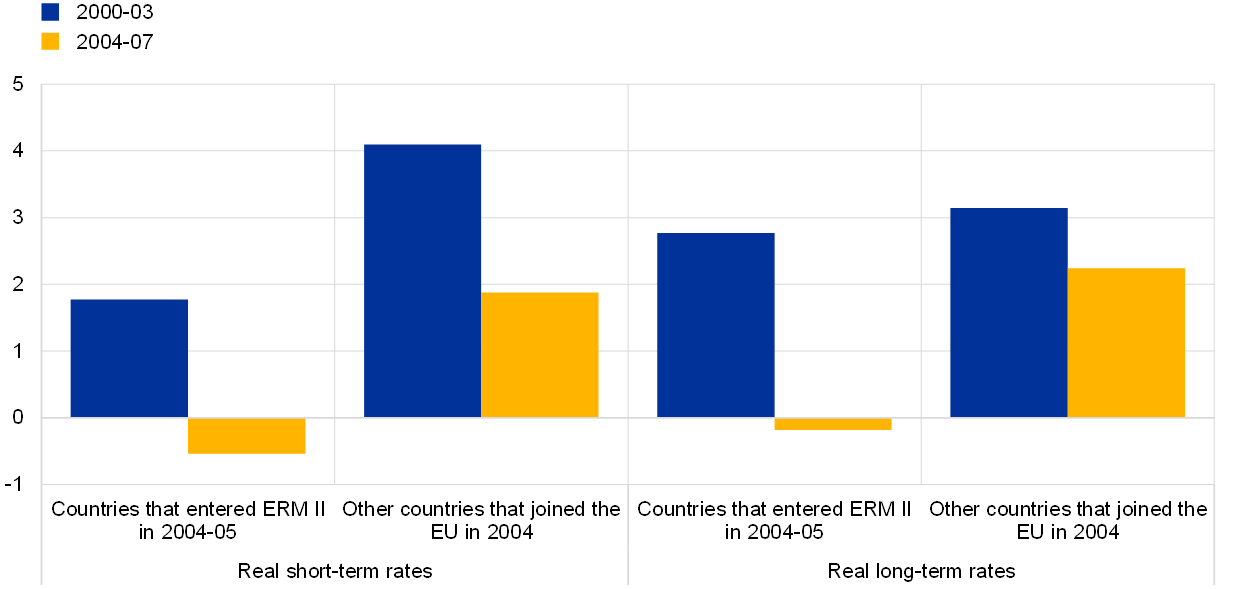

After joining the mechanism, ERM II participants also experienced a stronger expansion in domestic credit and lower real interest rates than CEECs that did not join ERM II after their accession to the EU. Large international financial inflows, particularly in the form of bank credit and other interbank flows, can exacerbate the domestic credit cycle, for example by supporting funding for banks.[14] Credit to the private sector as a share of GDP nearly doubled in ERM II countries in the five years after they joined the mechanism, while in the other CEECs the increase in credit stock was more gradual (see Chart 4). At the same time, ERM II countries experienced negative average short-term real interest rates in the three to four-year period after joining ERM II. In addition, the drop in long-term real interest rates was much stronger in ERM II countries than in non-ERM II countries (see Chart 5). While financially less-developed economies usually have lower domestic savings and therefore need financing from abroad in order to support economic growth and the overall catching-up process, this may pose a challenge for certain countries joining ERM II, as large international financial inflows are likely to fuel credit booms and busts.[15] Moreover, credit booms can turn out to be more severe and difficult to contain in countries with fixed exchange rates, as the rising inflation typically associated with strong domestic demand lowers real interest rates further and this in turn triggers additional credit demand.

Chart 4

Domestic credit to the private sector in ERM II and non-ERM II CEECs

(as a percentage share of GDP; unweighted averages)

Source: ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The ERM II countries covered are Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia and Slovakia. Period “t” is a country-specific event and identifies the year in which the country joined ERM II: 2004 for Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia, and 2005 for Latvia and Slovakia. The non-ERM II countries covered are Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. Period “t” is a country-specific event and identifies the year of the country’s accession to the European Union: 2004 for the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, 2007 for Bulgaria and Romania, and 2013 for Croatia.

Chart 5

Real interest rates in ERM II and non-ERM II CEECs

(percentages)

Sources: DataStream, ECB, Eurostat, OECD, Reuters, and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Nominal three-month money market rates and nominal long-term (10-year maturity) interest rates for convergence purposes are adjusted using the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP). Aggregates are simple averages across countries. The countries that entered ERM II in 2004-05 are Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia (all in 2004), and Latvia and Slovakia (both in 2005). The other countries that entered the European Union in 2004 are the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland. Data for real long-term rates are missing in 2000. Data for Slovenia are available from 2002 onwards. Estonia is excluded from the aggregate of real long-term rates owing to missing data.

3.3 Policy implications

Although the period following EU accession in 2004-05 fell within the environment of “Great Moderation”[16], which is very different from the conditions prevailing today, the empirical findings discussed in the previous subsection nevertheless carry some general policy implications that may be of relevance for Bulgaria and Croatia, as well as for other EU Member States that seek ERM II participation in the future. ERM II participants may benefit from increased availability of capital, but they may also face an increased risk of a build-up of macroeconomic imbalances. Countries with large international financial inflows are indeed more likely to experience credit booms and busts as foreign financial inflows increase the available funds of the banking system, of which a significant share is often foreign-owned in central and eastern Europe.

Historical experience suggests that factors such as resilient economic structures[17] and the quality of institutions and governance reduce the risk of economic imbalances and enhance the capacity of a country to cope with shocks. While the economic literature on this topic has mainly focused on the phase following euro adoption,[18] the evidence discussed in the previous subsection suggests that similar dynamics might also materialise during the run-up to euro adoption.

Resilient economic structures create the preconditions for allocating capital to productive firms, thus supporting the catching-up process rather than the formation of bubbles. This also allows policymakers to resist pressures of vested interests against the implementation of necessary reforms, build up fiscal buffers during upturns and implement other countercyclical measures, including on the macroprudential side. Developments such as a surge in the most volatile components of international financial flows may provide the wrong sort of incentives in a weak institutional context, thus leading to the postponement of reforms and deterioration in the country’s adjustment capacity. This is not to deny that developing economies need to attract capital. However, if institutions are weak, such financial inflows are more likely to eventually become a disadvantage more than a benefit.

The smooth participation of a given currency in ERM II therefore requires the proper framework conditions to be in place at the national level. The prospect of joining ERM II and then the euro area should serve as an important incentive to improve policies, governance and institutions in order to attain convergence on a sustainable basis – in a similar manner to the incorporation of European law when joining the EU. If these improvements do not take place, excessive ease of financing after joining ERM II – and later after adopting the euro – risks reducing the incentives to make necessary reforms.

4 The Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna in ERM II

In the summers of 2018 and 2019 respectively, following discussions with the ERM II parties, the Bulgarian and Croatian authorities made a number of policy commitments in areas of high relevance for a smooth transition process and subsequent participation in ERM II. After fulfilment of these so-called prior policy commitments, as well as the announcement of post-entry policy commitments to be completed after joining ERM II, the two countries entered ERM II and European banking union simultaneously on 10 July 2020. This section explains the rationale for ERM II participation and the roadmap towards it that was implemented for these two EU Member States.

When Bulgaria and Croatia first expressed their interest in joining the mechanism, ERM II parties took account of three fundamental considerations.

First, it would be the first time a country had joined ERM II since the financial crisis, from which important lessons had been learned. As a result, the European institutional framework had been substantially overhauled over the previous decade and it was crucial not to overlook the lessons learned in future ERM II decisions. The resilience of economic structures, financial stability and the quality of institutions and governance had moved to the forefront of discussions, given their importance for the longer-term sustainability of euro adoption. In particular, the experiences of former ERM II participants had confirmed that these features needed to be in place to ensure smooth participation in the mechanism.

Second, it would also be the first time a Member State had joined ERM II since the start of European banking union. In banking union, the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the Single Resolution Mechanism have direct powers over the banking system of the Member State concerned. Each Member State is required to enter banking union at the latest by the time it introduces the euro. Given that ERM II is a preparatory phase for euro adoption, joining ERM II today also means preparing for banking union. To this end, it was considered advisable for countries aiming to adopt the euro to enter into close cooperation with the ECB (see Box 1) at the same time as joining ERM II.[19]

Third, there was also a need to take account of country-specific considerations. While both Bulgaria and Croatia had made significant progress in addressing macroeconomic imbalances and both countries had a track record of adjusting to adverse shocks under their own exchange rate regimes, there were concerns about their smooth participation in ERM II, owing to a number of remaining vulnerabilities.

In this context, the question arose as to how the aforementioned considerations could best be accommodated within the existing institutional and legal framework. EU Member States must be treated equally at any given stage of EMU, which implies that no preconditions or new rules can be imposed before a Member State applies for ERM II participation. Any Member State is, therefore, free to request the inclusion of its currency in ERM II at any time and make its policy commitments, as other Member States have done in the past. At the same time and in line with the procedure recalled in Section 2.3, ERM II parties may decide not to agree to that Member State’s ERM II participation in the event that the policy commitments and related actions taken by its national authorities do not sufficiently address the identified developments, concerns and risks. This approach is fully consistent with the ERM II framework.

During the informal phase of the roadmap towards ERM II participation, a dialogue was held between the ERM II parties and the Bulgarian and Croatian authorities on the risks that had been identified and how they could be mitigated. This dialogue clarified the policy commitments that the Bulgarian and Croatian authorities would have to make and fulfil when moving forward with the roadmap. Once this phase was completed, the last step in the roadmap was marked by the formal requests for the inclusion of the Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna in ERM II, which were sent the day before the decision was taken.

Some policy commitments were completed by the time Bulgaria and Croatia formally entered ERM II (“prior commitments”) and, in line with past practices, other commitments have to be completed after joining ERM II (“post-entry commitments”), with the aim of achieving a high degree of sustainable economic convergence by the time of euro adoption. Both prior and post-entry commitments needed to be reasonable, proportional and motivated. They also had to be specific, realistic and verifiable in nature. Finally, it was agreed that they had to be implemented, monitored and verified in a relatively short period of time.

In the meantime, adequate monitoring was established by the ECB and the European Commission within their respective remits in order to verify compliance with both prior and post-entry commitments. In particular, the ECB focused on commitments related to the banking sector, including both banking supervision and macroprudential issues. Following a mandate issued by the ERM II parties, the Commission focused on commitments concerning structural policies. In order to forestall overlap with other procedures, it was also noted that fiscal policies are governed by the Stability and Growth Pact, and that the judicial reforms and the fight against corruption and organised crime in Bulgaria were monitored by the Commission under the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM).

Prior commitments were made by Bulgaria in the summer of 2018 and by Croatia in the summer of 2019, and completed by both countries before they joined ERM II on 10 July 2020. Three of these commitments were in the same policy areas for both Bulgaria and Croatia: (i) establishing close cooperation between ECB Banking Supervision and the national competent authorities (NCAs) under the legal framework of the SSM; (ii) strengthening the macroprudential toolkit by empowering NCAs to adopt so-called borrower-based measures, such as imposing limits on the debt service burden of borrowers relative to their income; and (iii) transposing EU anti-money laundering directives into national legislation. The other three commitments were country-specific and pertained to structural policies. Box 1 discusses these commitments in greater detail and describes the process of implementing and assessing the prior commitments falling under the ECB’s remit (i.e. those in the banking supervision and macroprudential fields), which were completed by the time the two countries joined ERM II. It also briefly explains how the supervision of non-euro area EU banks under close cooperation works in practice and how it differs from the supervision of euro area banks. Box 2 lists the structural policy-related prior commitments made by the Bulgarian and Croatian authorities, which fall under the remit of the Commission.

Box 1

Completion of ERM II prior policy commitments related to banking supervision and the macroprudential toolkit

The European Central Bank was mandated by the exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) parties to monitor the implementation of the two prior commitments related to banking supervision and financial stability, which the Bulgarian and Croatian authorities had to complete by the time they joined ERM II. The two commitments were: (i) to establish close cooperation between ECB Banking Supervision and the national competent authority (NCA) under the legal framework of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM); and (ii) to strengthen the macroprudential toolkit by establishing a clear legal basis on which to adopt macroprudential borrower-based measures, such as imposing limits on the debt service burden of borrowers relative to their income.

Bulgaria and Croatia submitted requests to establish close cooperation between their NCAs and the ECB in July 2018 and May 2019 respectively. Based on these requests, the ECB assessed whether the conditions for establishing close cooperation had been met. In accordance with the legal framework, the assessment consisted of two main parts: (i) a legal assessment of the relevant national law adopted by the requesting Member State, and (ii) a comprehensive assessment of credit institutions established in the Member State. To properly verify whether all conditions had been met, the ECB developed a standard assessment framework based on Article 7 of the SSM Regulation[20] and the procedural aspects specified in Decision ECB/2014/5 on close cooperation[21].

With regard to the legal assessment, Bulgaria adopted relevant legislation in December 2018, putting in place a mechanism to ensure that Българска народна банка (Bulgarian National Bank, BNB) would adopt any measures required by the ECB in relation to credit institutions. The ECB assessed the new legislation, including whether the powers available to the BNB would be at least equivalent to those of ECB Banking Supervision. In order to comply with the requirements for close cooperation, the BNB introduced a draft law in January 2020 amending the Law on credit institutions[22] and the Law on the Bulgarian National Bank[23]. The new law amended the sanctioning powers of the BNB and extended the list of breaches which may be subject to sanctions.

Similarly, the Croatian authorities amended the Credit Institutions Act[24] and the Act on the Croatian National Bank[25] in order to create a legal basis for close cooperation with the ECB. The first amendments were adopted by the Croatian Parliament in July 2019 and entered into force in August 2019. Additional amendments were adopted in April 2020 and entered into force in the same month. The ECB assessed the national legal framework as compliant with the relevant conditions for establishing close cooperation. The amendments ensured that once close cooperation started, the ECB had all the powers necessary to carry out its supervisory tasks vis-à-vis Croatian banks.

The comprehensive assessment results for Bulgarian banks were published on 26 July 2019 and indicated capital shortfalls for two out of the six participating banks.[26] The two banks implemented their respective capital plans before close cooperation was established. With this final step, all supervisory and legislative prerequisites were fulfilled. On 10 July 2020 the ECB announced that its Governing Council had adopted a Decision establishing close cooperation with the BNB[27].

The comprehensive assessment results for Croatian banks were published on 5 June 2020 and did not indicate any capital shortfalls for the five selected Croatian banks. On 10 July 2020 the ECB announced that its Governing Council had adopted a Decision establishing close cooperation with Hrvatska narodna banka (HNB)[28] following the latter’s fulfilment of all supervisory and legislative prerequisites.

When Bulgaria and Croatia expressed their intent to join ERM II, their macroprudential framework did not include a legal basis for borrower-based measures. Instead, the framework mainly relied on capital instruments based on the Capital Requirements Directive[29] and the Capital Requirements Regulation[30], such as the countercyclical capital buffer. Although both HNB and the BNB had broad powers to issue recommendations on new lending practices, these were not as legally binding and enforceable as borrower-based measures.

Against this background, both the Bulgarian and the Croatian authorities made commitments to broaden their macroprudential toolkit by providing the legal basis for borrower-based measures. This was completed through the adoption of the relevant legislation in December 2018 and April 2020 respectively.

After the completion of their prior commitments, Bulgaria and Croatia joined ERM II and banking union. From 1 October 2020 the ECB started directly supervising significant Bulgarian and Croatian institutions, while the Single Resolution Board became the resolution authority for these and all cross-border groups. Credit institutions falling under close cooperation are subject to the same supervisory standards and procedures as their equivalents in the euro area.

A key difference between Member States that have adopted the euro and those under close cooperation is that ECB legal acts, including decisions on banks, do not have direct effect in the Member State in close cooperation. This means that the ECB does not adopt decisions addressed to banks in these Member States, but rather issues instructions to the respective NCA, which will in turn adopt the required administrative measures at the national level.

The establishment of close cooperation with the BNB and HNB marks an important milestone in the development of banking union. It is the first time that banking union has been enlarged with EU Member States outside the euro area.

Box 2

Completion of ERM II prior policy commitments related to structural policies

In their letters to the exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) parties, Bulgaria[31] and Croatia[32] committed themselves to implementing a number of policy measures related to structural policies before joining ERM II. The European Commission was mandated by the ERM II parties to monitor the implementation of these prior policy commitments, in line with its remit. The monitoring was facilitated by regular technical exchanges between the Commission and the Bulgarian and Croatian authorities. The European Commission provided regular progress updates to the ERM II parties. At the same time, the ECB was reporting on the implementation of policy measures related to banking supervision and the macroprudential toolkit (see Box 1).

Bulgaria and Croatia each tailored their prior policy commitments on structural policies to their own national conditions in order to avoid a build-up of macroeconomic imbalances and to improve institutional quality and governance. The Bulgarian authorities made commitments to implement measures in the following policy areas: (i) the supervision of the non-banking financial sector, (ii) the insolvency framework, (iii) the anti-money laundering framework, and (iv) the governance of state-owned enterprises. Meanwhile, the Croatian authorities made commitments related to: (i) the anti-money laundering framework, (ii) statistics, (iii) public sector governance, and (iv) the business environment.

The final assessment reports were published together with the ECB Decisions to include the Bulgarian lev[33] and Croatian kuna[34] in ERM II. On 8 June 2020 and 19 June 2020 respectively, the Croatian and the Bulgarian authorities informed the ERM II parties that their prior commitments had been completed, except for those relating to establishing close cooperation with the ECB, and asked the ERM II parties to invite the Commission and the ECB to assess their effectiveness. Both institutions confirmed that the policy commitments in their respective areas of competence had been fully implemented and welcomed the efforts of Bulgaria and Croatia to better prepare their economies for smooth participation in ERM II.

Post-entry commitments made by Bulgaria and Croatia on joining ERM II

- The Bulgarian authorities made commitments to implement additional measures on the non-banking financial sector, state-owned enterprises, the insolvency framework and the anti-money laundering framework. Furthermore, Bulgaria will continue implementing the extensive reforms under the CVM in the judiciary and in the fight against corruption and organised crime.

- The Croatian authorities made commitments to implement specific policy measures on the anti-money laundering framework, the business environment, state-owned enterprises and the insolvency framework.

At the time of its inclusion in ERM II, the central rate of the Bulgarian lev against the euro was set at the prevailing market rate, which was the same as the fixed exchange rate under the currency board arrangement (CBA). With the adoption of the standard fluctuation margins of ±15% it was also determined, in line with past arrangements, that the Bulgarian CBA is a unilateral commitment borne exclusively by Българска народна банка (Bulgarian National Bank), which should place no obligation on the ECB or the other participants in ERM II.

The central rate of the Croatian kuna against the euro within ERM II was set at the prevailing market rate at the time of its inclusion. In line with past practice, the central rate was equal to the official ECB reference rate – published daily on the ECB’s website – of the Friday prior to the currency’s inclusion in ERM II. The inclusion of the Croatian kuna in ERM II is also subject to the standard fluctuation margins of ±15%.

Box 3 summarises the economic assessment supporting these exchange rate decisions.

Box 3

Assessing the central rates of the Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna within ERM II

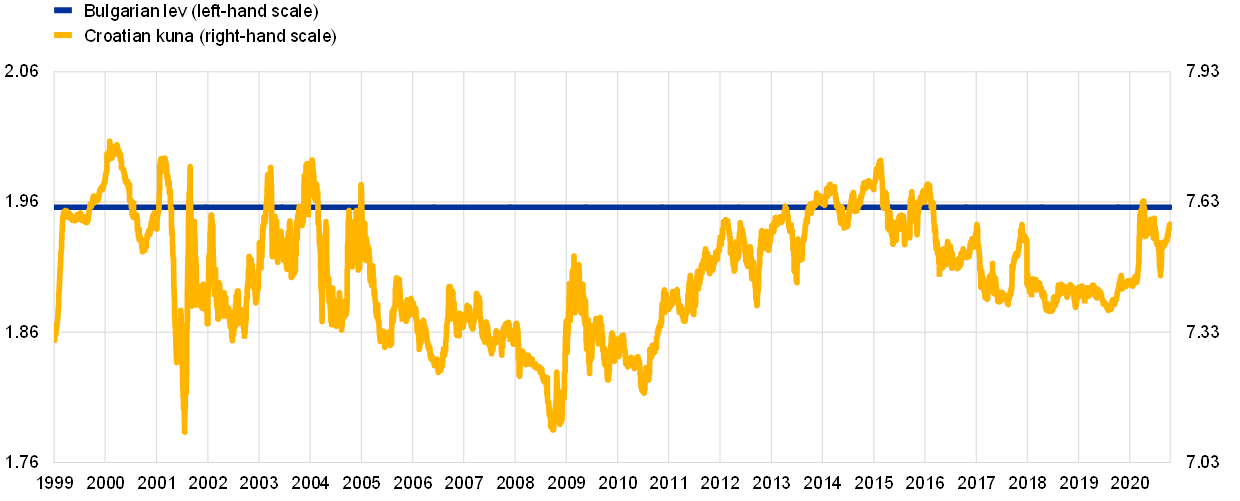

Bulgaria and Croatia have both maintained nominal exchange rate stability for more than two decades (see Chart A). Bulgaria adopted a currency board arrangement in July 1997 to address hyperinflationary pressure. This was initially based on a legal obligation of Българска народна банка (Bulgarian National Bank, BNB), enshrined in the Law on the Bulgarian National Bank, to exchange domestic currency at the rate of 1,000 old Bulgarian levs per Deutsche Mark. Following a (purely nominal) redenomination of the Bulgarian lev in June 1999, the fixed exchange rate was realigned to 1 new Bulgarian lev per Deutsche Mark. When the Deutsche Mark lost its status as legal tender in Germany in 2002, the reference currency was changed to the euro and the fixed exchange rate set at 1.95583 levs per euro, equal to the irrevocable conversion rate between the Deutsche Mark and the euro. The Croatian kuna has been trading under a tightly managed floating exchange rate regime since its introduction in 1994, with no pre-announced level, path or band, and its exchange rate against the euro has been fluctuating within a narrow range of ±4.5% around its average level since 1999.

Chart A

Exchange rates of the Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna against the euro

(4 January 1999 to 14 October 2020; national currency units per euro)

Source: ECB.

In line with its currency board regime, BNB frequently exchanges Bulgarian levs for euro in operations with domestic banks, while Hrvatska narodna banka (HNB) only rarely intervenes in foreign exchange markets. As stipulated by the Law on BNB, the monetary liabilities of BNB are fully covered by its foreign reserves and BNB is obliged to exchange monetary liabilities and euro at the official exchange rate. Thus, the issuance of Bulgarian levs is not discretionary, but directly linked to the availability of international reserves. As a result, BNB does not need to undertake traditional foreign exchange interventions in order to maintain the exchange rate peg. Instead, it issues or absorbs national currency solely against reserve currency in transactions with the banking sector, referred to as “type II interventions”, such that the national currency supply automatically equates to the demand. In the case of the Croatian kuna, interventions have historically been carried out both to support and to weaken the currency, although more recently, until the coronavirus (COVID-19) shock, HNB has mostly intervened in order to counter appreciation pressures.

As a result of their credible commitments to maintaining exchange rate stability, both national central banks have accumulated comfortable buffers of foreign exchange reserves. Since the global financial crisis of 2007-08, BNB and HNB have significantly expanded their holdings of foreign exchange reserves. In 2019 the foreign exchange reserves of BNB and HNB stood at 47% of GDP and 38% of GDP respectively and substantially exceeded all traditional metrics of foreign exchange reserve adequacy.

Equally, both countries have experienced significant improvements in their external balances since the global financial crisis, turning their current account balances from double-digit deficits into surpluses. Their net international investment positions have also changed significantly – from around -100% of GDP for both countries to -50% for Croatia and -30% for Bulgaria, making the latter one of the least vulnerable central and eastern European countries.

This rebalancing was also paired with significant adjustment of relative costs and prices, such that from a normative perspective the Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna were assessed to be in line with fundamentals. The assessment of both countries’ external balances when they joined ERM II suggested that their current account balances were relatively close to their cyclically adjusted level, and if anything somewhat above their medium-term current account benchmarks, thus indicating that the currencies were not overvalued. At the same time, both countries’ relative price levels were close to what their relative income levels would suggest based on a comparative econometric analysis. In 2019 Bulgaria’s price level stood at 52% compared with the euro area, while its real per capita GDP was 49% of that of the euro area. Croatia’s price level was 65% compared with the euro area, while its real per capita GDP was 60% of that of the euro area.

In the absence of any significant real exchange rate misalignment, the ERM II parties decided to set the central rates of the Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna at the level of their prevailing market rates. In the case of the Bulgarian lev, this was equal to its fixed exchange rate under the currency board arrangement. Thus, the Bulgarian lev was included with its central rate set as its fixed exchange rate of 1.95583 levs per euro. The Croatian kuna was included with its central rate set to 7.53450 kuna per euro, corresponding to the level of the reference exchange rate (as published by the ECB based on a daily consultation between European central banks) ahead of its inclusion.

Both countries were included in ERM II with a standard fluctuation margin of ±15%. At the same time, it was accepted that Bulgaria would join with its existing currency board arrangement in place as a unilateral commitment imposing no additional obligations on the ECB.

5 Conclusion: the way ahead and related challenges

Joining ERM II is a necessary step towards euro adoption. At present, 19 EU Member States have adopted a common monetary policy with the euro as a common currency. Under the Treaty, all other EU Member States except Denmark are expected to introduce the euro once the necessary requirements have been fulfilled.

From a procedural angle, the decision on euro adoption is taken by the Council of the European Union in line with the relevant Treaty provisions, including the need to stay in ERM II for at least two years. The process is defined in Article 140 and Protocol 13 of the Treaty and can be summarised as follows. After consulting the European Parliament and following discussion in the European Council, the Council shall, at the proposal of the European Commission, decide which Member States with a derogation fulfil the necessary conditions to adopt the euro. This decision is taken on the basis of the Maastricht economic and legal criteria. The Convergence Reports on the fulfilment of these criteria are prepared by the European Commission and the ECB. The Council shall act – on the basis of the recommendation of a qualified majority of euro area EU Member States – at the latest six months after receiving the Commission’s proposal, which is based on the conclusions of the Convergence Reports. The next Convergence Reports are expected to be published in the course of 2022.

From a policy standpoint, the adoption of the euro is an opportunity, albeit not a guarantee, for Member States to reap substantial benefits. Most importantly, the adoption of a global currency as legal tender fosters monetary stability, which in turn manifests itself in a stable and low real interest rate environment. This benefit, however, may also expose a country to vulnerabilities if it considers monetary stability as a substitute for disciplined and sustainable economic policies.

Article 140 of the TFEU states unambiguously that a country should achieve “a high degree of sustainable convergence” with the euro area before introducing the euro. This means that the adoption of the euro should be sustainable over the long run. Factors such as resilient economic structures, financial stability, the quality of institutions and governance, and the progressive enhancement of EU architecture also play a very important role. The convergence process, therefore, is not automatic, and at country level should be seen rather as a by-product of relentless policy efforts before and after adoption of the euro, i.e. as a continuum. It is for these reasons that the ECB press releases of 10 July 2020 on the inclusion of the Bulgarian lev and Croatian kuna in ERM II also emphasised a “firm commitment” by the respective authorities “to pursue sound economic policies with the aim of preserving economic and financial stability, and achieving a high degree of sustainable economic convergence.”[35]

The role of ERM II as a preparatory phase for euro adoption and the regime shift this entails raise policy challenges that need to be addressed. The prior commitments made by the Bulgarian and Croatian authorities in recent years have spurred the introduction of important measures that will mitigate risks under ERM II. The additional, structural policy measures announced when they joined ERM II are therefore to be welcomed. However, while crucial steps have been taken in both countries to address macroeconomic imbalances, there is still significant progress to be made with regard to the overall quality of institutions and governance. In this regard, taking a long-term view on policymaking will be decisive going forward, especially in the light of the new divergence risks caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19) shock.

Finally, these policy efforts will also need to include measures aimed at preventing the euro changeover from being used by firms and price-setters as an excuse for unwarranted price hikes that may harm the trust of the population in the single currency. In this regard, the national authorities, in cooperation with the European Commission and the ECB, can benefit from past experiences with euro changeover in other countries, which have included measures such as public campaigns and the introduction of dual price display, as well as agreements with relevant associations. The ECB is fully committed, along with the Commission, to supporting the Bulgarian and the Croatian authorities in the promotion of campaigns to prevent the rounding up of prices.

See the box entitled “The Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna in the exchange rate mechanism (ERM II)”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB, 2020.

Until 10 July 2020 Denmark was the only non-euro area EU Member State participating in the mechanism. Since then the ERM II parties have also included Bulgaria and Croatia.

Article 140 and Protocol 13 TFEU state that euro adoption by a given Member State is subject to the fulfilment of several economic and legal (Maastricht) convergence criteria. In their biennial Convergence Reports, the ECB and the European Commission examine whether (i) the countries concerned have achieved a high degree of sustainable economic convergence, (ii) the national legislations are compatible with the Treaty and the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the ECB, and (iii) the statutory requirements are fulfilled for the relevant national central banks to become an integral part of the Eurosystem.

With regard to exchange rate stability, the ECB and the European Commission examine whether the country has participated in ERM II for a period of at least two years without severe tensions being observed in the normal fluctuation margins of the exchange rate mechanism. In particular, this means that the country should not devalue the bilateral central rate against the euro on its own initiative during this period. Protocol 16 TFEU grants an exemption to Denmark from participation in Stage Three of EMU. Denmark is, therefore, the only non-euro area EU Member State to participate in ERM II without pursuing the objective of euro adoption.

More generally, on 1 January 1999 EMS was replaced by Stage Three of EMU.

Resolution of the European Council on the establishment of an exchange-rate mechanism in the third stage of economic and monetary union, Amsterdam, 16 June 1997 (OJ C 236, 2.8.1997, p.5).

While narrower bands are as a rule adopted on a unilateral basis, i.e. without imposing any additional obligations on the remaining participating NCBs or the ECB, they can be multilaterally agreed in the case of economies at a sufficiently advanced stage of economic convergence, as was the case with Denmark.

See “Policy position of the Governing Council of the European Central Bank on exchange rate issues relating to the acceding countries”, ECB, 18 December 2003.

For recent reviews of the benefits of euro adoption, see the speech by Mario Draghi entitled “Europe and the euro 20 years on”, on accepting the Laurea Honoris Causa in Economics from the University of Sant'Anna, Pisa, 15 December 2018, and Brans, P., Clemens, U., Kattami, C. and Meyermans, E., “Economic benefits of the euro”, Quarterly Report on the Euro Area, Vol. 19, No 3, European Commission, forthcoming.

Despite increasing evidence that global “push” factors, rather than country-specific “pull” factors, are the main driving forces of international capital flows, the interaction of country-specific characteristics with global trends may play an important role in determining the dynamics of international capital flows. See, for example, Rey, H., “Dilemma not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence,” speech at the Jackson Hole Symposium of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 2013.

As the countries under consideration joined both the European Union and ERM II in 2004-05 (except for Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia), these developments also reflected business cycle synchronisation to some extent.

Countries participating in ERM II also experienced larger international financial inflows than the other CEECs in net terms.

The insignificance of EU accession for international financial inflows holds true if the ERM II participation dummy is dropped from the specification.

See, for example, Lane, P.R. and McQuade, P., “Domestic Credit Growth and International Capital Flows”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 116, No 1, 2014, pp. 218-252, who also find that domestic credit growth in European countries before 2008 was strongly related to net debt inflows but not to net equity inflows.

The experience of credit booms in the new EU Member States during the 2000s has been widely discussed. See, for example, Backé, P. and Wójcik, C., “Credit booms, monetary integration and the new neoclassical synthesis”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 32, No 3, pp. 458-470, and Bakker, B.B. and Gulde, A-M., “The Credit Boom in the EU New Member States: Bad Luck or Bad Policies?”, Working Paper Series, No 10/130, IMF, 2010.

See Bernanke, B.S., “The Great Moderation”, remarks at the meetings of the Eastern Economic Association, Washington, DC, February 20 2004.

The expression “resilient economic structures” is used in Juncker, J.-C., Tusk, D., Dijsselbloem, J., Draghi, M. and Schulz, M., “The Five Presidents’ Report: Completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union”, Background Documents on Economic and Monetary Union, European Commission, 2015. In Brinkmann, H., Harendt, C., Heinemann, F. and Nover, J., “Economic Resilience: A new concept for policy making?”, Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2017, economic resilience is defined as “the capability of a national economy to take preparatory crisis-management measures, mitigate the direct consequences of crises, and adapt to changing circumstances. In this regard, the degree of resilience will be determined by how well the actions and interplay of the political, economic and societal spheres can safeguard the performance of the economy – as measured against the societal objective function – also after a crisis”.

See Fernández-Villaverde, Garicano, J.L. and Santos, T., “Political Credit Cycles: The Case of the Euro Zone”, NBER Working Paper, No 18899, 2013; Challe, E., Lopez, J and Mengus, E., “Southern Europe’s institutional decline,” HEC Research Papers Series, No 1148, HEC Paris, 2016; Masuch, K., Moshammer, E. and Pierluigi, B., “Institutions, public debt and growth in Europe”, Working Paper Series, No 1963, ECB, September 2016; and Diaz del Hoyo, J.L., Dorrucci, E., Heinz, F.F and Muzikarova, S., “Real convergence in the euro area: a long-term perspective”, Occasional Paper Series, No 203, ECB, December 2017.

At the same time, entering into close supervisory cooperation without joining ERM II is also a possible course of action for EU Member States that are currently outside the euro area, i.e. the two processes do not necessarily need to be synchronised.

See Council Regulation (EU) No 1024/2013 of 15 October 2013 conferring specific tasks on the European Central Bank concerning policies relating to the prudential supervision of credit institutions (OJ L 287, 29.10.2013, p. 63).

Decision 2014/434/EU of the European Central Bank of 31 January 2014 on the close cooperation with the national competent authorities of participating Member States whose currency is not the euro (ECB/2014/5) (OJ L 198, 5.7.2014, p. 7).

Law on Credit Institutions, adopted by the 40th National Assembly on 13 July 2006, published in the Darjaven Vestnik, issue 59 of 21 July 2006.

Law on the Bulgarian National Bank, adopted by the 38th National Assembly on 5 June 1997, published in the Darjaven Vestnik, issue 46 of 10 June 1997.

Credit Institutions Act, published in the Narodne novine No 159/13, 19/15, 102/15 and 15/18.

Act on the Croatian National Bank, published in the Narodne novine No 75/08 and 54/13.

See “ECB concludes comprehensive assessment of six Bulgarian banks”, ECB Press release, 26 July 2019. The two banks with capital shortfalls in the comprehensive assessment were First Investment Bank AD and Investbank AD.

Decision (EU) 2020/1015 of the European Central Bank of 24 June 2020 on the establishment of close cooperation between the European Central Bank and Българска народна банка (Bulgarian National Bank) (ECB/2020/30) (OJ L 224I, 13.7.2020, p. 1).

Decision (EU) 2020/1016 of the European Central Bank of 24 June 2020 on the establishment of close cooperation between the European Central Bank and Hrvatska Narodna Banka (ECB/2020/31) (OJ L 224I, 13.7.2020, p. 4).

Directive 2013/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms (OJ L 176, 27.6.2013, p. 338).

Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms (OJ L 176, 27.6.2013, p. 1).

See the letter from Bulgaria on ERM II participation of 13 July 2018.

See the letter from Croatia on ERM II participation of 4 July 2019.

See the ECB press releases “Communiqué on Bulgaria” and “Communiqué on Croatia” of 10 July 2020.